Trebuchets, Cows, and Horror of War - Sieges in Games and History

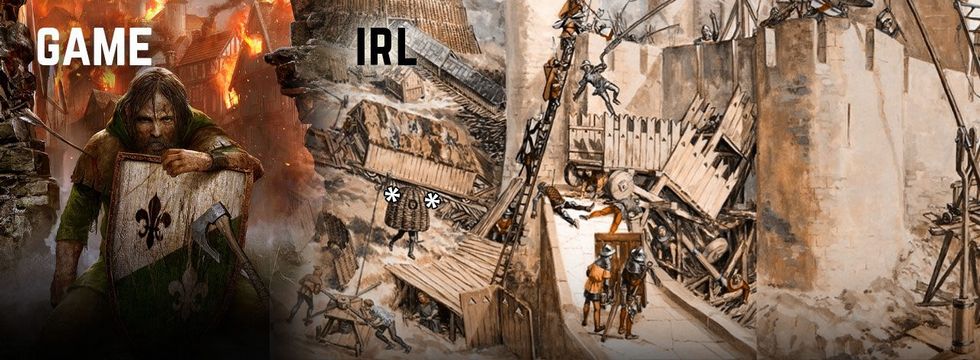

Spectacular scenes of castle sieges can sure be entertaining, but in reality, they were a slow process, full of dread – let alone for the civilians. Playing the upcoming Siege Survival: Gloria Victis I wondered – how different are games and history?

- Trebuchets, Cows, and Horror of War - Sieges in Games and History

- From ladder to the (so-called) catapult

- If not up, then down, or...

Assaults and sieges of medieval fortresses are a cherished subject in literature, film, and art. Many of us remember the brilliantly realized sequences of the attack on Helm's Deep in The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers or the capture of Jerusalem in Kingdom of Heaven. The usual scenes of fighting between soldiers are accompanied by huge machines or cunning tactics of the defenders, such as pouring hot tar from the walls. The battle scenes of capturing castles are simply more spectacular, mainly because action is condensed in a small area and various gadgets in the form of battering rams, catapults or siege towers.

The gaming world also tries to emulate these scenes, but so far, the less visually spectacular genre of strategy achieved best results, as exemplified by the Stronghold series. Castle sieges were also introduced in various MMOs, such as Age of Conan, Guild Wars 2 or The Elder Scrolls Online, as well as the sandbox game Mount & Blade. Still, we're yet to receive a real, high-budget game that would feature sieges as spectacular as in Hollywood.

An original approach to sieges is presented in the upcoming Siege Survival: Gloria Victis. Inspired by critically-acclaimed This War of Mine, its creators show us sieges from the point of view of civilians trying to survive in a fortress separated from the world. They get by away from the walls, where the bulk of the fighting takes place, trying to help the wounded, get food and provide other resources needed by both the soldiers and inhabitants of the fortress. It doesn't mean their lives aren't at risk, though; they experience quite similar problems as front-line soldiers, because, as we should see, conquering a fortress was not always as straightforward as killing all the defenders.

So what did real medieval sieges really look like? Did they actually pour hot tar on soldiers? Were Monty Python kidding when they depicted launching cows with siege engines? Let's examine how cities and fortresses used to be captured in times of primitive combat.

Time, and weapons of mass destruction

One thing worth getting out of the way first is that there weren't really that many textbooks on sieges back in the day – most of them were a long and complicated combination of some, or most of the methods listed below, in varying proportions. There were also exceptions and strongholds that fell quickly due to one action or another, but these were isolated cases. Not all castles surrendered to the enemy, though every fortress was in theory conquerable, even those with the thickest and highest walls.

How? A castle is generally a building designed to keep unwanted people from entering it, so a frontal attack was really a last resort. Generally, the most effective way to capture a stronghold was to cut off the defenders' food supply and starve them out. That's why many sieges in the Middle Ages lasted a really long time – though this is mostly true of larger cities. There, supplies of drinking water were much more readily accessible, oftentimes employing secret tunnels and sea access for smuggling provisions in, and the potential fields withing the city walls, as well as livestock, ensured some self-sufficiency. This, combined with the functional design of a castle and its walls, greatly extended the defense capabilities.

However, the final outcome depended on a myriad of other factors. Sometimes, the starved army surrendered the fortress, sometimes it was the attackers who had to let go. Starvation often proved to be an effective weapon against smaller strongholds that could not be conquered by direct means. When neither ladders, battering rams, siege towers, nor undermining could do the job, blocking access to food often ended the affair, if only after several additional weeks. An even more effective way was to cut off the source of drinking water, for example by seizing the aqueduct supplying it to the town/fortress. That's actually how the huge Krak des Chevaliers castle in Syria fell, despite having food in store for a good five years. In Siege Survival: Gloria Victis, there is huge emphasis on food gathering and production, which seems quite apt.

Besieged for decades

The longest siege in history is taken to be a series of blockades of the Spanish city of Ceuta in northern Africa by Moroccan forces with English support. The entire operation lasted a total of 33 years, from 1694 to 1727. In the first phase, it defended until 1720, and, thanks to the arrival of reinforcements from Spain, repulsed the enemy. An outbreak of plague in the city, however, forced the Spanish commanders to retreat. Without them, Ceuta lasted another 7 years before the Moroccans finally withdrew, though mostly due to then ongoing, internal power struggle.

The second was the siege of Kandia – from 1648 to 1669, 21 years. At the time, Kandia was the main city in Crete and belonged to Venice, and the attacking side was Turkey (supposedly one of the pretexts for the siege was the Knights of Malta attacking a Turkish convoy and taking over the Sultan's harem). Despite attempts to cut off food and water supplies and a bombardment that lasted 16 years, Venice managed to hold the city. After 1667, regular siege operations began, which, combined with the betrayal of one of the engineers building Kandia's fortifications, caused the commander of the Venetian forces, short on food and weapons, to finally surrender the city four years later.

Subsequent sieges were not as long-lasting – usually ranging from 8 to 12 years or less.

Cow catapult – true story?

Starvation was not the only "weapon of mass destruction" forcing the defenders to surrender the fortress. A disease outbreak was even more effective. Although piles of corpses alone were often enough to cause an epidemic and there was no way to carry them out of the castle, attackers were eager to accelerate the spread of sickness. And here, we come to the question of how much credibility was there in the scene with the cow catapult in the movie Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

The famous comedians admitted that the idea was their own invention, simply because it seemed particularly amusing and bizarre. However, we don't have to bother wondering whether cattle was indeed used as cannon fodder; using animals in general as disease-spreading projectiles was common enough. Let us skip here the detail that in the movie in question, it were the attackers that were bombarded with cattle (and other livestock) by the castle crew.

Attackers often flung carrion, large vessels of excrement, and even decaying corpses behind the walls to create biologically hazardous conditions. "Weapons" like these became especially deadly when a rotten load hit a well or other source of drinking water. It's worth emphasizing that what today seems a silly joke of Monthy Python, was a source of perhaps agonizing terror for inhabitants of a besieged city.

It wasn't always about causing a small epidemic right away. Throwing various abominations over the walls was also part of psychological warfare, designed to crush the morale of the defenders. Severed heads and dismembered bodies of messengers or POVs were catapulted to the other side. Pots with venomous snakes or scorpions were also used in warmer regions of the world.

The animator Terry Gilliam also cited an interesting story about another use of dead animals in sieges. The story was that during the Battle of Carcassonne in France, after a year's siege, the defenders started running out of basic necessities. They allegedly decided to go all-in, and try to deceive the attackers. They killed the few pigs they had and stuffed them with the last of the grain. Then, they launched these at the besieging troops with the clear message: we have so much food we can use it as projectiles. The ruse supposedly worked and the enemy retreated from under the walls.

So, if famine and pestilence were so effective, why were there direct battles at all?