If not up, then down, or.... Trebuchets, cows, and horror of war

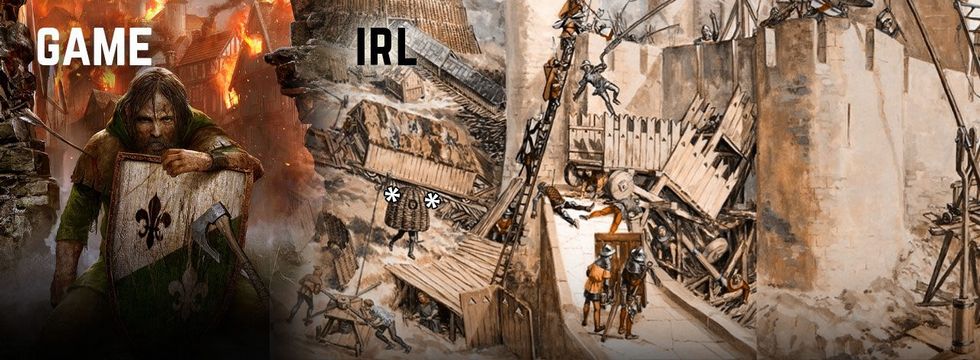

- Trebuchets, Cows, and Horror of War - Sieges in Games and History

- From ladder to the (so-called) catapult

- If not up, then down, or...

If not up, then down, or...

So, since shelling strongholds was neither effective nor profitable, perhaps there was another way? Indeed – attack from below! "Sapping" consisted of digging under the walls of fortresses, usually to set fire to the wooden reinforcement of the tunnel, weakening the foundations and helping to tear down that wall. Later, underpasses were used to blast the fortifications with gunpowder. This technique was used during the first siege of the fortress of Rochester in 1215, after a long and fruitless bombardment with trebuchets. As a result of undermining, nearly a quarter of the structure collapsed. Another example is the capture of Castle Gaillard in Normandy in 1204. The troops of King Philip II of France undermined the main tower, leading to its collapse. However, this is another strategy that's time-consuming and may not always be used.

...with cunning and treachery

Was there even an ideal way to capture a fortress? Without sacrificing many casualties and tearing down the entire building? Yes, but it was unpredictable, and not universally available, and always different – we're talking about human, with it's cunning and vulnerabilities. It would be trivial to bring up Odysseus and his "commandos" locked in the Trojan Horse. So let us recall the siege of Castle Gaillard in Normandy again. After the tower was demolished by undermining, Philip's soldiers began to look around for a weak point in the structure. One of them discovered a latrine outlet that led to the chapel. This is how the medieval spec-ops got into the castle and, silently eliminating a few guards, opened the drawbridge to let in the rest of the army.

On the opposite side of clever ideas, however, is human weakness, usually leading to exploitation and betrayal. This was the case, for example, during the Crusader siege of Antioch in 1098, and over 500 years later, when the Corfe Castle fell during the English Civil War. In June 1643, nearly 600 "roundhead" soldiers (supporters of the Parliament) began a siege of the fortress defended by Lady Mary Bankes with only a handful of faithful soldiers. Using methods like hurling rocks and hot coals, the crew held out until August, and managed to kill over 100 attackers. Unfortunately, Lady Mary was betrayed by one of her officers, who allowed the hostile troops to infiltrate the castle. As a token of recognition for their heroic defense, the victors not only spared her life and liberty, but also allowed her to keep all her titles and land.

Gloria victis or vae victis?

Sparing the lives of defenders was not such an uncommon event, which somehow contradicts the common opinion about the cruelty of medieval times. Acting at the behest of the commander, soldiers were common folk, usually far from the heartless bandits raiding the highways. Although there were, of course, instances of bestiality and genocides, conquering a city or fortress did not immediately imply razing the buildings and butchering the people. Especially the army that had to continue the conquest was quite limited in its capabilities, and usually ended up refilling provisions and setting out. The end of a siege also often meant complicated negotiations of various terms of surrender.

Glory to the victors, glory to the vanquished

The times of conquering cities and capturing fortresses did not end with the medieval era. Even the development of firearms and the widespread use of cannons did not lessen the importance of a thick, defensive wall. Instead, reports of these more inhumane methods, such as bombardment with carrion, corpses, or feces, have faded over the centuries – pests found their way anyway. Amidst the cinematic and spectacular siege towers, engines, and ladders, it's worth bearing in mind that each such event carried with it the timeless horror of war, horrible suffering of each side: the attackers, the defenders, and the civilians caught in the middle.