The dawn of Steam? The Netflix of gaming is getting closer

Although the hegemony of Steam is unquestionable today, it’s quite possible that within the next decade, the platform will actually share the demise of boxed games that it created itself.

A decade and a half ago, when Steam was debuting, a few game developers quietly mentioned the prospect of a future, where video games are not purchased in boxes, but rather downloaded from virtual accounts – straight to the user’s hard drive. The concept seemed somewhat sci-fi-ish; there were not too many people who really believed that such a scenario will actually come true.

In reality, a chain reaction was provoked back then, and it snowballed with an awesome momentum: physical distribution is dying away and it’s not even able to do that with dignity, as most boxes just contain Steam codes. Things are somewhat different on consoles, but keeping in mind that Microsoft launched the Xbox Game Pass last year, and considering how well all digital stores are doing, the demise of physical distribution is on the cards. Only the greatest optimists could predict otherwise.

Buying digital games (or rather “lending” – bear in mind that you’re not paying for the right to own a game, but rather to use it) doesn’t have to be the final stage of the distribution model’s evolution. Indeed, if you have a look at the practices of some developers, as well as the music and motion-picture industries, the assumption that within the next few years we’re in for another – albeit less drastic – revolution, which this time will shift the bulk of the market to subscription-based services, is only natural.

Gaming Netflix

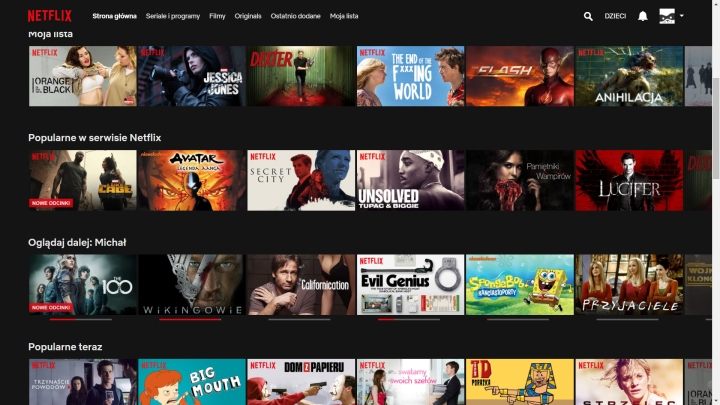

Before resurrecting witch burning practices and grabbing pitchforks and torches to fight another attempt at robbing us if our right of ownership, let’s stop for a second and think whether subscription-based gaming is really such a bad thing. Just take a look at Netflix – for an equivalent of two cinema tickets, a movie on DVD or half of a Blu-Ray, you get unconstrained monthly access to thousands of movies and series, all in good quality and usually localized – all just a few clicks away. Same story with Spotify, which even in its free version offers an enormous music library, which – if you’re willing to spare the coin (and again, you pay less than for a new release on CD) – is enhanced to higher quality and free of ads.

These services utilize smart policies to attract audiences – they offer ultimate convenience and an alluring price-to-content ratio. For a small fee, you get access to huge pop culture libraries, assembling which would be nearly impossible in physical form. Saying that we easily get used to such convenience is a major understatement. I can tell looking at myself: I love completing DVD collections with my favorite movies, and countless boxes embellish the shelves in my room – still, I often prefer to just play them from Netflix, because it’s quicker.

So, if they charge 20 dollars a month for full access to, say, a thousand games – including the hottest new releases, which cost around $60 – it’s not bad at all, huh? I would strongly advise against boycotting a service that offers a deal like this one, especially if you would get the DLCs, too.

Streaming

The future of gaming lies not only in subscriptions, but also (and perhaps mostly, in the long run) in data streaming. In a nutshell, the technology allows games to run on servers, only sending the image to the end user – just as if it was a movie. The machine the player is using, on the other hand, feeds their input to the server. Streaming would allow you to play even the most demanding games on a computer that wouldn’t be able to run Euro Truck Simulator on low settings (well, I might have exaggerated, but you get the point).

The only catch here is the Internet access. Such quantities of data will require a very stable and a very fast Internet connection in order for the experience to be reasonably fluent. And “reasonably” here still means a noticeable lag; streaming might work well for turn-based strategies or adventure games, but with fast, reaction-based games, it just doesn’t deliver. This is just one reason allowing to assume that subscription services will dominate the market much sooner.

Which doesn’t mean no one’s trying to develop sufficient technology. PlayStation Now (which has been working in the States for a few years) combines streaming with subscriptions, allowing players to access hundreds of classic games for a monthly fee, and stream them on PlayStations and PCs; also, selected games purchased on Steam or some other uPlay, if they’re too demanding for the customer’s machine, can be run on Nvidia’s servers and then streamed to the user’s computer, using GeForce Now.