Pandora’s boxes - how many times do we have to pay for a single game?

Paid loot crates with randomized content in full-price titles are old news by now. The problem begins when we take a look at what’s in them and the companies’ willingness to exploit our penchant for gambling. Is this just another way to make us pay more?

Long ago car companies found a way to sell their products for twice the price. The trick was to “enhance” basic car models with stylish rims, different paint colors, leather seats, parking sensors, navigation, and so on; the price of the extras, though, could sometimes amount to a second car’s worth of money. Video game publishers have relied on a similar method for some time now, offering premium, deluxe, or limited editions, along with paid DLCs and preorder bonuses in addition to “standard” editions. The trick remains the same – you end up paying the company much more than you could have paid. Lately, however, even that is not enough for some companies. There were several titles in which we were not just encouraged, but outright forced to pay a second time for a game, or the company was simply trying to squeeze as much money out of us as it could.

One box – two problems

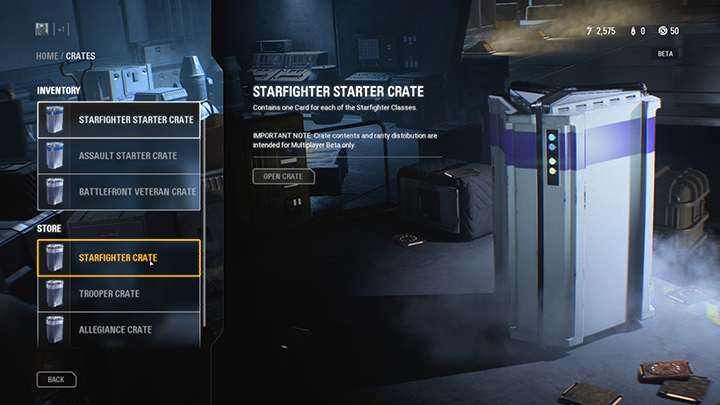

Random loot boxes, our topic for today, are nothing new in video games. In the past, though, they were associated only with an “optional” payment method in free-to-play titles. Some time later, the games came to offer packs of visual bonuses, such as skins, which probably was attractive only to the most hardcore fans of a given title. Currently, we are witnessing something more – progressively daring attempts by the industry to sell loot boxes as an essential gameplay element of the biggest, most popular full-price titles.

The era of overpriced horse armor is long gone. Now, you’d have to pay for a “rider’s chest”, giving you a 1 in 15 chance to get an armor, and a 14 in 15 chance to get pink reins or magical sugar that will give your horse a +3 bonus to speed. For now, the public outcry and the first attempts to fight the new business strategy have focused mainly around the thesis that no matter how you slice it, the whole thing looks like gambling; and one aimed at underage gamers at that.

FROM MMORPGS TO RACING – THE HISTORY OF THE LOOT BOX

The idea for paid crates with random content came from MMORPGs and their loot drop systems – mechanics of acquiring equipment for the character during the game. At first it was a means of monetization in mobile games, 2007 ZT Online being the first game to actually use it. Various other Asian video game developers have quickly caught up, introducing this solution to their own games, and the 2011 Puzzle&Dragons became the first game to earn one billion dollars solely on microtransactions from item boxes.

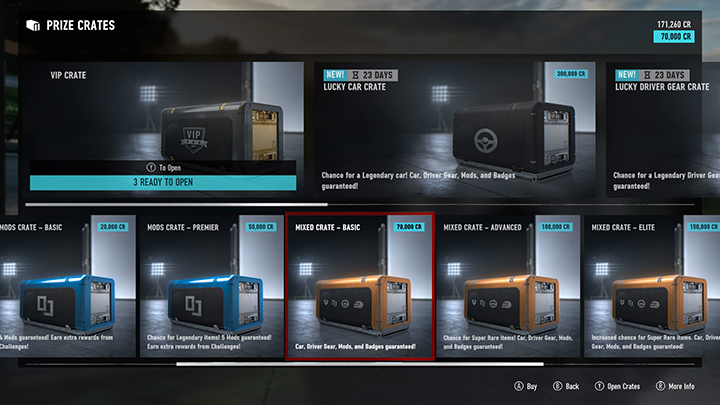

The crates started appearing in Western games courtesy of Valve, which introduced them to their multiplayer FPS Team Fortress 2 in 2010. MMOs, such as Star Trek Online or Lord of the Rings Online, followed. All of them, however, were free – the point of “Stop right there, buddy!” was first crossed by Electronic Arts in 2012, as the company included paid item boxes in the multiplayer mode of their then biggest full-price title, Mass Effect 3. Not much later and we had “weapon crates” all over CS:GO. Today, the loot box mechanics can be found even in racing simulations.

It appears, though, that the risks and dangers related to gambling are just a part of the problem, which may now backfire at titles that relied on randomized loot crates for a long time. The other important aspect is the actual worth and usefulness of the content we pay for. We no longer pay just for cosmetic items for hardcore fans, but also for things that actually modify game mechanics and make things easier for us, even in single player mode – just like in free-to-play mobile games. This year, randomized crates have appeared (or will appear) in so many new titles that it becomes clear that the developers are probing the market and gamers alike for the exact amount of additional money they may be willing to pay for their already bought game. Even if the client has already bought an “elite veteran’s deluxe premium edition”.

The publishers swear to all that they hold dear (probably money) that each and any random item pack that can be bought is completely optional, and the game can be completed without buying even a single box. The facts are, however, that reaching the finale without spending some cash will take much longer in some games (such as in Middle-earth: Shadow of War), or the game will be reduced to mindless grind (NBA 2K18), or our character will be visibly weaker than others, whose players parted with their cash, which not so long ago seemed to be the case with Star Wars Battlefront II (we’ll see whether it remains that way once the game is released).

In short, we mean a situation when the companies intentionally make our games a chore, so that we, frustrated and angry, pay extra money to have the game work the way it should have worked from the start. You can’t really call that gambling – the sweet uncertainty of reward is replaced by angry waiting for what we should have got the moment we paid a full price for a game. Anger and frustration, however, are hardly reflected in statistics and it’s tricky to measure or otherwise prove them, so the majority of protests revolve around the first part of the issue – gambling. Do random loot boxes really equal gambling? Will somebody do something about it in the near future? And why did surprise crates suddenly appear in so many titles?

Why do we even buy crates?

To be honest, you can see where the profit-hungry corporations are coming from. If they introduce various optional paid content into their games, some players, no matter the outcry and amount of backlash on the Internet, will buy it; and they can buy a lot. Even devs themselves remember cases like that of a Mass Effect fan who spent thousands of dollars on trading cards, as described by an ex-Bioware employee. Just drop by Overwatch forums to learn the reasons why we eagerly spend the extra cash. We also have to remember that the majority of users playing popular titles remain silent, be it on forums or in the comment sections. There are, however, various reasons why we buy extras or cosmetic items in video games.

Many treat exotic, rare skins (serving as trophies and a symbol of possessing something unique) as a collection that just has to be complete. Gamers from the US think that spending 50-60 dollars once in three months is not a big deal for them, since they have jobs and pay their own bills. Others claim that it’s the way they show their support for the developer whose game won their sympathy. Yet others simply want to skip the annoying grind and get their rewards faster and without as much effort. But that’s just some of our motivations: the conscious ones that depend on our decisions. Apart from them, however, there is a group of hidden mechanisms of the human psyche: all that, which is ruled by our subconsciousness, and what we are unaware of, especially when we’re young.

Sudden gift in the form of rare skins, accompanied by an array of audiovisual effects prompts our brain to react the same way we do when being rewarded – e.g. by releasing increased amounts of dopamine. The feeling of uncertainty and the promise of a grand reward amount to a process that gives us a lot of pleasure, which is why we are so eager to throw the dice one more time, for example by buying a new batch of randomly generated loot boxes. The entire thing has a flipside, though: if we do not get what we want for an extended period of time, our frustration will grow, we will be buying more and more in a frantic attempt to get a payback, find our promised prize, and get another dose of dopamine.

Both negative and positive stimuli form the standard mechanism that leads to forming an addiction. <br>A strong-minded person will call it quits after buying two or three boxes full of useless stuff. Unfortunately, some people will simply keep buying until they get what they want, and then the whole process repeats for a new item. Now, let’s have the equation include items that somehow gained actual, real-world money value (like in CS:GO or PUBG), and here we are: dangerously close to actual gambling. It’s not about the pleasure of winning a unique award anymore – we are playing to gain something worth a certain amount of real money. Despite that, the lawmakers were reluctant to recognize gambling in random loot box mechanics from video games.

BOX GAMBLING OUTSIDE OF GAMING

The emotions connected to randomized content or the human penchant for gambling are exploited not only by video game publishers, but also by online shops that sell games! Popular websites selling serial keys, such as G2A or Kinguin, offer packages containing a completely random set of serial keys for games available on Steam or Origin. The packages are sold for a few Euros and under attractive names, such as “Hot Random Game” or “Premium Steam Keys”. The comments on the Internet, however, say that the packages contain mostly titles that are either available for free or cost a few cents. And if you buy more packages, you’ll notice that many of the game titles repeat.

Crates are (technically) not gambling

If the law doesn’t recognize loot box mechanics as gambling, neither can organizations that rate video game content, such as PEGI or ESRB. It’s no wonder then that their answer to the question whether loot box mechanics are a form of gambling was “no”. The lawmakers classify them as booster packs for card games rather than slot machines, regardless of the fact that they work on a similar principle as the latter.

Video game publishers reject having their products compared to slot machines, their line of defense being the fact that every microtransaction ends with the buyer receiving some kind of item – completely ignoring the said item’s actual usefulness. One more essential element comes in the form of inability to directly trade (in game) items from boxes we bought for cash, Steam Wallet being the best example here. That said, using video game items for lotteries where you pay real money on third-party websites is clearly recognized as gambling.

The latest example of the aforementioned lotteries can be drawn from the recent CS:GO Lotto gambling scandal, where one could use weapon skins gained in the game to win large amounts of real dollars. The affair became widely known after it was revealed that the owners of the site were in fact famous streamers who encouraged their followers to take part in “their” lottery. Eventually, the whole thing was swept under the rug after a short period of media outrage. Some of the websites vanished, and the youtubers involved either expressed their deepest apologies or tried to cover their tracks. Even Valve, the company that created most of the controversial weapon skins, had to answer to the law. The answer, though…

In response to the Washington State Gambling Commission’s demand to remove the option to trade skins in Counter-Strike, thus eliminating any chance to organize gambling lotteries, the owners of Steam expressed their “deepest regret and disappointment about being accused of such conduct”. Next thing they did was to prove that both Steam and CS:GO were perfectly in accordance with the law of Washington D.C. state, and that the independent activities of third-party gambling websites damaged the company’s good name. Valve denied having had any connections, profits, or having promoted gambling websites that used weapon skins from CS:GO, and stated that it was prepared to defend its good name in the court.

The new wave mob

That’s how things looked by the end of 2016, when it seemed like the debate about random loot and gambling (which cast a shadow on many other games as well, such as DOTA 2, EVE Online, or Team Fortress 2) died down a little. Little did we know, as a new wave was just around the corner. It came in the form of games that didn’t employ microtransactions or loot box mechanics up to that point, but the stunning success of games like Overwatch has worked up everyone’s appetite for profits. By now, crates full of randomized content have made their way into games like Forza Motorsport 7, Star Wars: Battlefront II, or Middle-earth: Shadow of War. Except their reception, as I’ve mentioned earlier, is anything but warm. Instead of being a nice small addition, their presence has spoiled the games for some of the players.

While the loot crates in Counter-Strike and Overwatch seem to be cleverly luring the player with a sweet promise of unique, perhaps even precious, but always optional content, those from Battlefront II or Shadow of War are more about cornering you into buying as they laugh at you. The necessity of reducing artificially inflated playtime or strengthening the character for it to be competitive in multiplayer has nothing to do with being rewarded. It’s just a method of making us pay for the game to work as it should be working. No wonder then that such conduct has sparked an outcry in the gaming community, and it’s much bigger than the one we witnessed during the CS:GO scandal.

Crates in the Parliament

In addition to the many outraged voices of famous and influential youtubers, the whole situation also resulted in certain questions being submitted to the highest legislative bodies. All the accusations revolved around gambling – specifically, making minors pay for unknown content and causing the risk of addiction. This is the path the UK players chose. Their online petition quickly gathered the required number of votes for consideration by the government, and one of them even asked a Labor MP to become their proxy. The MP, in turn, then addressed the Minister of Digitization, Culture and Media. The questions concerned the steps the UK government would be taking to protect minors from gambling related to the purchase of random items in computer games.

<br>Of course you should not expect a quick reaction in such cases. Lawmakers are acting as if they were stuck grinding in a game without the help of those infamous boxes which can speed things up. For the time being, we've only learned that the UK government treats the protection of minors against gambling in gaming very seriously, and that websites that deal with the exchange of virtual items for money without the required licenses are under fire. The issue of buying crates in games is a completely different matter, which the British government intends to look into.

In the wake of all this buzz we found out that the small Isle of Man, which is not officially part of the United Kingdom and even has its own parliament, is the only place in the world where paid items from games (including crates) are subject to gambling law. In Japan, in turn, it was legally forbidden to place individual items in separate crates, completion of which provided an extremely rare and therefore more valuable object. Unfortunately, many developers have found ways to circumvent this regulation.

In May China adopted a law requiring that all crates in games published there should have a clearly defined likelihood of drawing rare items. Interestingly, what developers are forced to disclose on China's territory is not necessarily the same they must do in other countries, where they can still control the frequency of getting more valuable skins by players. There are also successful attempts to circumvent this provision (for example, Hearthstone players in China officially cannot buy card packs, only a specific amount of arcane dust, to which a bonus is added... in the form of a pack of cards. Aren’t you crafty, Blizzard).

Will video games become a paid service?

We can't expect any meaningful changes unless legislative bodies of the most important markets, that is United States and European Union, come together and create a legal policy regarding lootboxes or, at least, follow in China's footsteps. We should also remember that any potential regulations won't remove all microtransactions, loot crates, skins and associated gambling elements from games. There will always be someone willing to get them, just like there are always people queuing to a casino.

This is more about limiting the access to the world of gambling for the underage players as well as discouraging publishers from what they are currently doing – placing content that is important for game mechanics in lootboxes. The possible necessity of placing a gambling-related PEGI icon on a video game box or rating Overwatch, a colorful shooter, "R" would surely prove problematic for the big publishers. And then there’s us – the consumers – who decide what we want to spend our money on. However, considering the diversity of our actions and expectations, we may only do something meaningful if we complement legal regulations.

Maybe we already lost in the same way we lost the fight for not breaking games into pieces and season passes. Games released by big publishers are inevitably becoming a service for which we may have to pay periodically in one form or another. When that happens (or when it will happen) we should feel that we spend money on new, attractive and carefully created elements rather than felling forced to pay in order to get rid of frustration or not because we’re not able to complete it otherwise. We can't do nothing about whether lootboxes and microtransactions become a standard in video games. However, we may have enough influence to at least choose their content and what we are willing to pay for.