Electronic art. The history of Electronic Arts studio

- History of EA - From Table-top Fail, to Legends, to... Anthem

- Electronic art

- "It's in the game!"

- The Golden 90s

Electronic art

After four years, Trip left Apple to start his own business. On 28 May 1982 he founded Amazin' Software. Hawkins didn't have a game, but he knew how to run a business. He started hiring his first employees (graphic designers, programmers, advisors) first from his own home, and then from the office lent to him by Don Valentine – a future investor. For the first six months, Hawkins used all of its savings up – for employee salaries, computer rental, the rent, etc. It wasn't until December 1982 that he obtained additional sources of funding, and in May the following year, the first games appeared under the banner that was already saying "Electronic Arts." Business started to grow.

TOP FIVE

The first games by Electronic Arts were five titles originally released on Apple II and 8-bit Atari platforms. These were: Archon: The Light and the Dark (chess-based), Axis Assassin (arcade shooter), Hard Hat Mack (a spin on Donkey Kong), Worms? (a game about developing your own bug, not to be confused with Worms 2-D artillery tactical game) and M.U.L.E. (four-players economic strategy).

One of EA's greatest successes of that period was Pinball Construction Set.

Working for Apple, a company founded by Steve Jobs to realize his outlandishly detailed and visionary ideas allows Hawkins to learn more about the people, who create hardware and software. They appeared to him not less as craftsmen and more as artists, or even stars the like of Hollywood and music celebrities, so he applied the same strategy in his own company, as people making music or movies would. Hawkins introduced notions of "producers" and "directors" to the gaming industry, soon adopted by the rest.

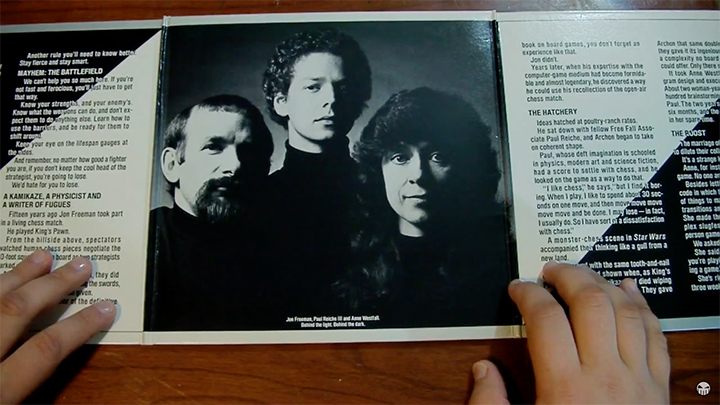

The fascination with the music industry was best evidenced by the appearance of the first Electronic Arts releases, which looked exactly like long-play vinyl. Flat, gatefold boxes the size of LP contained a professionally cropped photo of the developers, like a mini poster of the biggest rock stars of that time. The idea was so good that other companies started to imitate it.

References to the music industry go further. Hawkins even hired employees using the same kind of contracts as record companies. It was basically a combination of a music-industry contract with an Apple's engineering contract, embellished with some original clauses meant for computer games only. Electronic Arts paid developers a certain amount upfront ($14k in case of Hard Hat Mack) to display capabilities and commitment, and then each artist had a share in the profits. The contract template created by Electronic Arts became almost universally adapted in the entire game publishing business for the following 15 years.

Reach, yes; but flexibility?

Electronic Arts under the watchful eye of Trip Hawkins demonstrated remarkable adaptability in keeping the market's whims in check. Games of all shapes and sizes were created to probe the audiences, test ideas and increase the success ratio. These productions were developed for the most popular platform first, and only then were converted to others. The first such core platforms were Atari 800 and Apple II, quickly replaced by Commodore 64, then to Amiga, and finally the PC. The consoles weren't initially in EA's scope of interest, but when Nintendo started shaking the American market, the priorities quickly changed. Hawkins didn't want to accept the strict Nintendo exclusivity that would bar his games from the main competitor – SEGA. In 1989, EA teamed up with them to create games for the first 16-bit console, the Genesis, only just announced.

The success in Genesis came in 1991, mainly thanks to a series of sports games. Before that happened though, EA changed the attitude towards Nintendo, releasing a few games on the NES, and then, with the release of the 16-bit SNES, Nintendo abandoned their exclusivity policy. Another good example of flexibility is that EA quickly diversified. They released one of the most popular graphics editors of the era, Deluxe Paint for Amiga.

BUYERS' MARKET

Hawkins recalls how painful it was for some developers to make games on cartridges. Many titles had to be adapted to new capacities and controllers, e.g. by completely redesigning the screen interface. Trip insisted that you have to make games for consoles that people actually owned, rather than suggest them buying another platform (PC). Some people hated the idea so much that about 30 of the 200 employees left Electronic Arts.

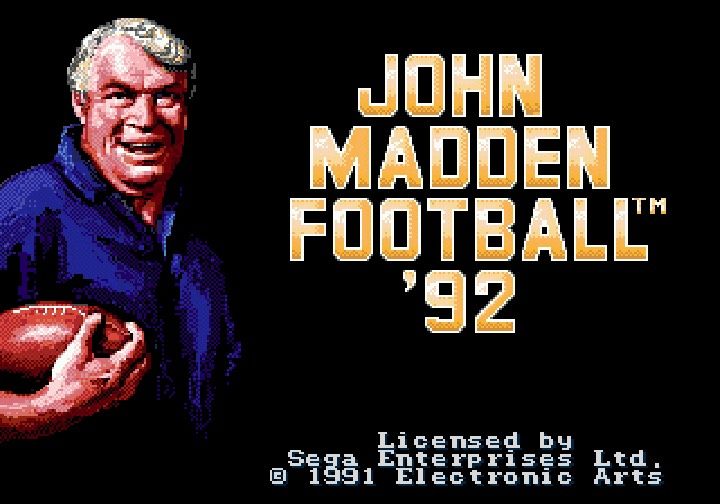

Soon thereafter, the company gave up the idea for making stars out of computer nerds. Instead of the names and faces of designers or programmers, boxes focused on building brand awareness and cooperating with real stars. The first attempt took place as early as 1983, when the game One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird was released, featuring real basketball stars of the time. It quickly escalated, reaching some of the most recognizable names in the business: Michael Jordan, Chuck Yeager (the first man to break the sound barrier), iconic chess player Garry Kasparov, or John Madden, coach of Oakland Raiders. This last name is particularly significant, as took the company across the Rubicon...