4A – how I invented moral choices. Does Your Voice Matter? Discussing Choices in Video Games

- Does Your Voice Matter? Discussing Choices in Video Games

- 1A – what's the difference between a good choice and a bad one

- 2A – an example of poor moral choice

- 3A – how to make a moral choice more difficult?

- 4A – how I invented moral choices

- 5A – why choices have little impact?

- 6A – impersonal summary

4A – how I invented moral choices

ON THIS PAGE YOU'LL FIND

We have already established that mechanics (rewards or punishments) and morality may prompt us to make one choice or another. I personally dealt primarily with the latter, since I was working with designers, who added mechanical features to the stories I wrote. They balanced penalties and rewards in such a way that the whole game would not prove too easy or too difficult. My job was to determine exactly which choices would be beneficial and how.

War isn't fair

First of all, when writing, you have to always keep in mind the broad assumptions of the entire project. The board game This War of Mine is an inherently difficult and sometimes unfair game. An important part of it is trying to show players what war looks like from the point of view of a civilian. That is: ugly.

I tried to convey that through a certain unpredictability. There have been times when players have been faced with a choice where one option seemed riskier than the other, and I have a few times deliberately made the safe options more problematic in the long run. Other times, I opted for the oposite. What I was interested in was making it difficult for players to preditc which choice would benefit them more.

This approach makes sense on a case-by-case basis, but the lack of logic and any consistency could be annoying. Unless explained with story, the consequences of our choices have to be logical. They don't have to be identical on all occasions, but it's good to use the "Chekhov's rifles" skillfully. If something is going to happen in the story, in should be telegraphed to the player beforehand. This only reinforces the plot twists.

Justice in the courtroom

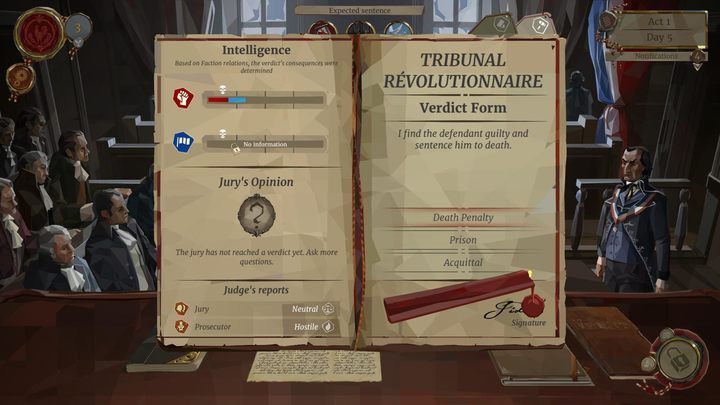

In We. The Revolution, I designed some of the court cases in which the main was the judge. The historical realities made him care more for the satisfaction of particular social groups and for the pursuit of his own interests, than for justice.

As I was writing the scirp, I never knew what circumstances a player would be in when taking on the given case. Should they please the revolutionaries, or would it be better to appease the common people? Therefore, I again focused on the moral side, and tried to create cases where both sides of the dispute were right to some extent.

A car owner accusing a servant who killed a horse and destroyed the vehicle out of carelessness; the servant's defense being the fact he was told to drive across the entire town, even though he had never done so before. An encyclopedist who beat up a colleague for plagiarism, or a conflict between a building owner and an architect, with a construction disaster and victims in the background.

Life brings a lot of inspiration every day. Just remember that both sides are right and that the final judgment is not entirely clear. It's a good example, because in this game, possible choices had their personifications. There was an alleged perpetrator and an alleged victim. In the case of each decision, you have to consider not only the consequences in terms of mechanics, but also in moral categories.

Thank you for listening to me, and since you've been so kind, you get to decide now.

- Do you want to go further and find out why there are so few choices in games, and when they are, they're often superficial? Head to part 5A on Page 6.

- Want to go back and analyze more examples from big and famous games? Go to part 4B on this page.

4B – more examples of good and bad choices

Zero immersion

Let us begin with an example, in which material benefit completely overshadows moral issues. Mount and Blade. We visit villages here and have the opportunity to either peacefully trade in them, or rob, or even ransack and burn them down. Destroying all the possessions of virtual settlers usually didn't prevent me from choosing the latter. If my gang was strong enough, I would steal everything I could.

From a moral standpoint, I was a monster who regularly destroyed the same villages dozens of times. But there was nothing there to convince me that I was burning actual villages. A single artwork showing a burned-down village is hardly causing moral anguish. We need to get to know someone before we care about them. That's why killing any of the characters in the first minutes of a game, movie or book isn't a great idea. Such an event carries zero gravity, because the character means nothing to us.

Sheer morality

WARNING! Spoiler alert – Far Cry 3

Another extreme example of the balance between mechanics and morality is the choice at the very end of Far Cry 3. We have to decide whether we want to save our friends or join a tribe of warriors alongside whom we fought for the whole game.

In terms mechanics, this choice is irrelevant. It's the end of the game anyway, and we know it. The choice carried some moral weight, but since I was aware that the game will end in a few minutes regardless of my decision, it didn't really matter.

By the way, I wanted to say a few words in defense of the plot in Far Cry 3. The main character found himself in a no-win situation, and the only way to survive was by transforming from an ordinary, civilized man into a callous murderer. In the end, he has to decide what's more important to him. His old life and the people for whom he has changed, or the new world and the violence, which is so poisonous it made him forget what he'd been fighting for. Since the game was focused on entertainment alone, killing could be fun, and we really could forget why we were doing this.

Punishment and reward

If the game gives us choices that involve both mechanics and morality, it usually means that we will be somehow punished or rewarded. Remember Army of Two: the 40th Day? There, for example, you could kill a white tiger in a cage to get a very good sniper rifle, or spare an innocent and harmless animal to walk away with nothing.

If we choose this approach when creating a game, we can decide to reward the player for decisions that are morally right. Maybe we can teach them something. We can also give rewards for snapping and doing something terrible, because in the end, a healthy person will feel bad about murdering a digital pet (harmless one at that). That's how we test resilience against temptation. How far can one go? In both cases, however, it will be a cliché, because in fact the choice ceases to be a moral one. If it becomes obvious that we choose between black and white, between a reward in the game and lack thereof, then the artificiality of the situation will only remind us that it's just a game.

This shows a kind of a dead end in game design, and it makes sense to invent choices that are truly ambivalent in moral terms.

- Since you didn't want to read about my experiences before, now I'm not going to give you a choice. Go to part 5A on Page 6.