SPARX – a game designed to fight depression. Game therapy – 7 games to combat depression

- 7 Video Games to Help Fight Depression

- Flow – Nuclear Throne

- Purpose – Stardew Valley

- Contact, sense of belonging –World of Warcraft

- Cognitive stimulation – Baba is You

- Flexibility – Dark Souls

- SPARX – a game designed to fight depression

SPARX – a game designed to fight depression

The antidepressant effect of all of the above games stems from some aspect of their gameplay and is neither deliberate, nor proven to work. Games generally work well for the brain, so it's safe to say that they may actually be helpful for certain groups. But what if somebody decided to develop a game from beginning to end designed to combat depression, measuring its effectiveness with the scientific method? Well, a game such as SPARX would be produced.

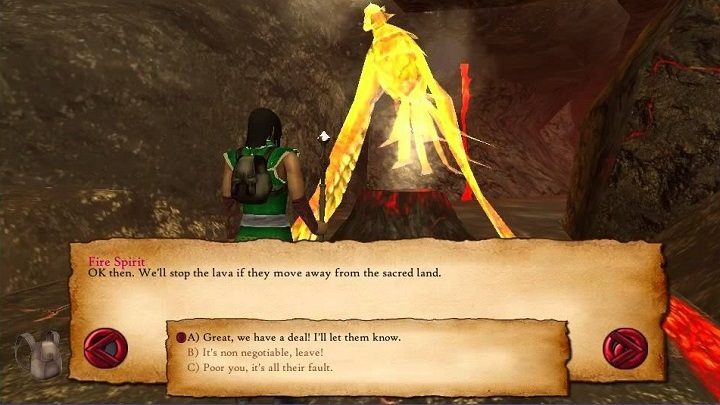

SPARX (Smart, Positive, Active, Realistic, X-factor thoughts) was released in 2013, designed by clinicians at the University of Auckland. The game is a fantasy RPG that tells the story of the struggles of the inhabitants of a fantastic realm with disgusting creatures known as GNAT (Gloomy Negative Automatic Thoughts). The game is based on the paradigms of behavioral-cognitive therapy, which claims that one of the causes of depression is nonadaptive automatic thoughts that appear in the minds of patients beyond their control.

The therapist's job is to teach the patient to cope with such thoughts (e.g. responding to "I'm hopeless" thoughts with remembering one's achievements and real skills). So players must literally kill the negative thoughts using unassuming, behavioral-cognitive techniques.

According to the authors of SPARX, the antidepressant efficacy of the game is 44%, but this applies to a specific groups of patients – eligibility was preceded by a personality test.

MODALITIES OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

The behavioral-cognitive therapy cited here is not the only treatment through psychological impact. While it may seem to be most effective at combating depression, the popular theory stating it is the only form of psychotherapy with scientifically proven effectiveness is simply a lie – there is evidence for the positive effect of every accepted modality. What's more, the evidence is similarly weak (due to the difficulty in investigating such a complex phenomenon as psychotherapy). Let's look at these other modalities.

Psychodynamic therapy refers to psychoanalytic theories and focuses on the patient/therapist relationship. The dynamics between them, defined by the ominous terms Transference and Counter-transference, is intended as a major source of information about the patient's mental life and a vector of therapeutic interactions.

Systemic therapy, in turn, assumes that mental disorders are resultant of a flawed system in which a person operates – family, work, or society. The symptoms of diseases, according to this theory, have a function that they perform in the system. For example, a child has anxiety attacks so as to focus the attention of parents, draw them away from their quarrels.

Humanistic therapy is now increasingly recognized not as a separate modality of therapy, but as a kind of subjective approach to the patient that should be implemented in the work of each practitioner. The integrative approach, in turn, focuses on the constructive combining of the above.

SPARX challenges players/patients with tasks that are meant as a metaphor for their problems arising from the disease. Game as a cure?

Even though a game designed as an antidepressant exists, you have to remember that psychology and pharmacology remain viable and effective means of combating depression – everything else is meant as aid. Such aid can, of course, be very helpful in therapy. Without social support, hobbies, and physical fitness, people often end up on a slippery slope that inevitably leads to relapse even after effective treatment.

When considering positive and adverse effects of electronic entertainment on the mood, it is worth thinking about what sort of fulfilment they let us achieve. On the one hand, we all know that games are meant to be fun. So is there any definitive recommendation? In a way, yes – it's that we all have our favorite games. Ones that aren't boring even after 200 hours. So if you ever feel kind of blue, don't feel guilty about getting back to these games. Every now and then, it's good to take a break from life. Just remember about taking breaks from playing.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I'm doctor of medicine currently obtaining specialization in psychiatry. Of course, I do not recommend games to my patients as cure, but psychotherapy teaches that human actions often have deep motivations – so it may turn out that seemingly casual entertainment actually performs incredibly important functions for some people. That's why talking about video games in my office doesn't seem out of place to me.

I played most of these games myself. I only missed World of Warcraft because of my allergy to subscriptions and MMO, but I included it as the first game that comes to mind when you think about games for socializing. But the rest – I've played these games, and can recommend them, with one exception. Dark Souls is an experience rather than a game. Enchanting with a wonderfully melancholic atmosphere, captivating with creativity and hellishly unpleasant on the gameplay side. And yet, I remember it fondly – when I see bits of the game or screenshots of it, I immediately locate the place and the context, which I don't think happens with other productions. That's why I decided to put Dark Souls on the list – it's an ambiguous game, but it certainly stays with you.