The Problem With Games Isn't Politics - It's Lack Thereof

Why the social issues? Why the politics? Hands off our favorite medium – I read under half of the news from the gaming world. And each time, I think to myself that someone obviously missed the moment when video games became political.

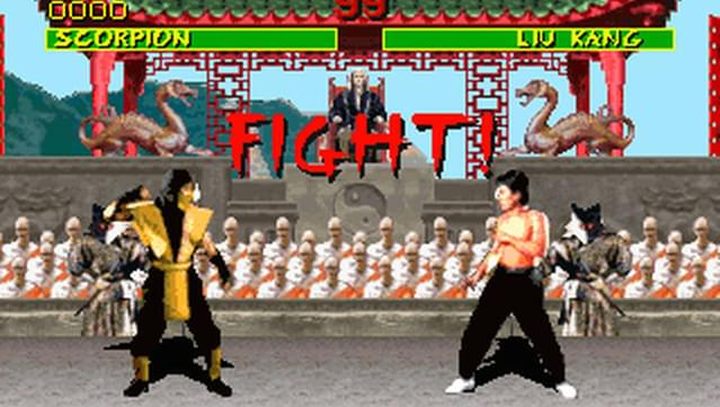

December 7, 1993. Senator Joe Lieberman begins questioning video game developer industry representatives before the U.S. Congress. Reason? The outcry over the realistic depiction of violence in the first installment of the Mortal Kombat series, as well as in the now-forgotten Night Trap (an equally ambitious and entertaining attempt to combine multimedia entertainment with cinematography). A few months later, during another interrogation, the shooter Doom is added to the list of threats to the moral standing of humanity. It's hard to know if anyone tells Sen. Lieberman to "keep politics out of our games." But if he does hear it, he probably can't even imagine that 30 years later, thousands of gamers will be making similar statements – not in order to get conservative politicians to leave their medium alone, but rather to curb the game developers who infuse games with serious messages and tackle real problems, which can apparently cause distress in some individuals.

Let's be honest here – how many AAA releases in recent years witnessed some sort of politically motivated backlash? The developers probably see that coming, allowing the player to play a female character, or create a character with a gender identity they see fit, or, for example, murder Nazis as a Polish-Jewish American, or fight a bunch of religious fanatics in Montana. As these games become announced and advertised, social media and sites like Metacritic start resonating with the phrase: "Keep politics away from games." In fact, all it takes sometimes is a more or less innocent easter egg for a shitstorm to break out online.

And sure, I can understand that some people are tired of the constant ideological battle. You can't even open a fridge nowadays without being labeled as radical. However, the world of games is rich enough that one can easily find a production that will provide blissful escapism, without any serious references to reality. You can focus on purely skill-based e-sports games, you can reach for a whole bunch of titles completely devoid of content and serving only brainless entertainment, or you can, for example, forget about the fact that the fantastic Dead Cells was created by a bunch of anarcho-syndicalists, and just die happily, time after time, without bothering with any of it.

I also have no problem with ridiculing these attempts to put highly political or social content into games. Because sometimes, it's hard to treat it seriously – such as in Assassin's Creed Syndicate, where we were literally running around the place with Karl Marx, killing exploitative, bloodthirsty capitalists for him.

The problem I have concerns something different altogether. Namely, the fact that the people screaming in all caps in the comments about politics in games don’t really want a choice between purely entertainment-oriented video games, and video games that are trying to say something important about the world we live in. For the most part, by the way, these are the most politically engaged people, who don't shy away from extensively discussing political issues on social media. Their intention is solely to limit video games as a pop-culture medium, to cement them as completely safe entertainment.

And that's where we've gotta talk about the elephant in the room. Not only have video games surpassed the movie and music industries over the past few years in terms of profits and audience size, but they have also become the dominant medium in terms of their impact on pop culture. In fact, you don't have to think about it for too long to realize it's true. It is simply a fact. At the same time, they're still a recent form of entertainment, and as such, they enjoy much more freedom from business and culture taboos. They're profitable enough to offer an experience worth millions of dollars, and they can still get away with offering it in a more controversial way. They also have something that other types of entertainment lack. Video games not only let us transpassively participate in the experiences of "the other" – they let us become the other.

Half a century ago, the most prominent film directors of the era like Kubrick or Hitchcock would likely sell their souls to the devil to have such a tool at their disposal. A way to not only show, for example, the horrors of war, but also to give the viewer a sense of how deceptively satisfying pulling the trigger can be, and how devastating consequences it can bring. Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899), Francis Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979), and the video game Spec Ops: The Line (2012) are in fact one and the same story, only in different forms. And only one of these works, even if artistically shallow, puts you in the middle of action. It's a very crude, brusque lesson in empathy, but a lesson in empathy nonetheless.

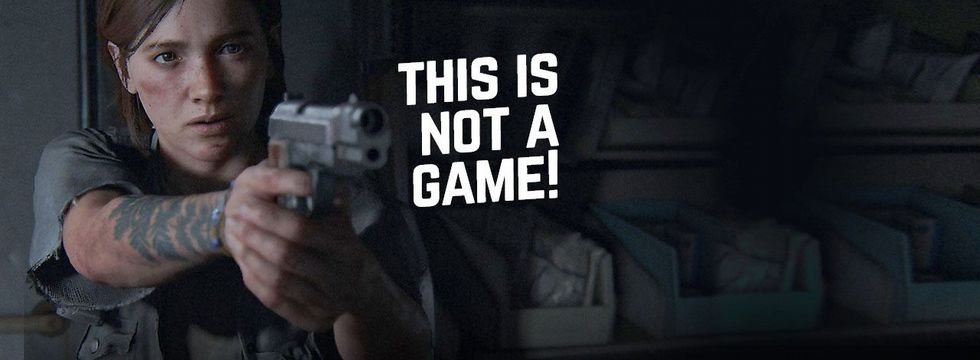

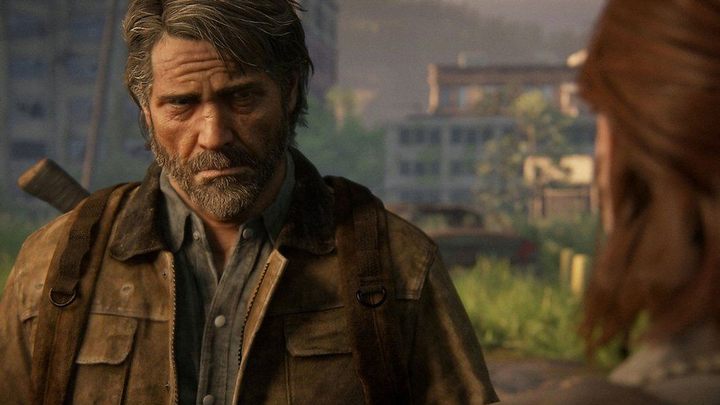

Which reminds me: No other work of art in recent years – not a book, nor a movie – has delivered for me such powerful and profound an experience as last year's The Last of Us Part 2 – a strongly polarizing game, exactly because of its political dialectic. And I'm not going to repeat here the arguments that everyone interested in gaming has heard dozens of times. I'll just point out one thing: practically all of the criticism leveled against Naughty Dog's work, both directly related to the social issues raised in the game, and those more veiled, such as the way the storyline was handled, can be summed up in one short sentence: "It wasn't fun, it wasn't entertainment."

And I do agree. Playing The Last of Us: Part II was also a difficult, sometimes even painful experience. Just as reading Cormac McCarthy can be a painful experience, for example, which undoubtedly inspired the authors, by the way. But these books are not read to spend a pleasant evening; they're read to learn something about the human condition. That people don't seem to understand this simple rule is evidenced, for example, by the regurgitated phrase saying that this game “is about revenge." Well, no, it's not a game about revenge – it's a game about the source of violence in a tribalized world, about how hatred spins out of control and how difficult it is to break away from its viscous circle. A game is therefore a way to enter this circle yourself; to feel, not just watch it from afar. I played it on the spot, on release day, and it still gives me food for thought today. Because the themes and message of The Last of Us: Part II are simply very relevant, rooted in today's reality and saying something about us.

And hence the title. I would like more games like this. And I know that I'm not alone in this desire. What if someone wants to play just for mindless fun? They don't want to think, experience, tamper with serious matters they think they've sorted out? Sure. There are thousands of games for just such players. My hearty request is that they left ambitious games to ambitious people. Both when it comes to consumers and developers. That's all I ask for.