Inside Review – enthralled by the creators of Limbo

For the last couple of years Playdead have been working hard on a new title, a follow up to the success of Limbo. Inside is the outcome. This is a gloomy journey of a little kid into the world of unethical human experiments.

The review is based on the PC version. It's also relevant to Switch version(s).

- Atmosphere;

- Design and visuals;

- As always with Playdead, the riddles are well designed and implemented;

- You die less often than in Limbo;

- The finale is a bombshell – like a good horror or a post-apocalyptic anime.

- Could have been a little longer;

- Borrows a bit too much from Limbo?

What is Denmark famous for? Well, apart from LEGO blocks there’s also The Olsen Gang, as everyone knows. And if they don’t, they ought to get acquainted with the movie, because those guys are the funniest bunch of wannabe crooks the TV has ever seen. On the other end of the spectrum we have Agent 47 – the cold professional from IO Interactive is, apart from Peter Schmeichel and Egon Olsen, the most recognizable Danish “export good”. A couple of years ago, another source of national pride appeared: Limbo – a dark platformer, basically a simulator of dying, in which we control a boy with a big head, trying to guide him through a path full of dangers.

Six years have passed since the release of that game. A big, well-paid studio could produce two AAA titles during this period time. Meanwhile, Playdead needed exactly six years to finish their next project. Back in 2011, Dino Patti, head of the studio, has announced that Project Two – as Inside was previously referred to – is in an advanced stage of development. For some reason though, it took another five years to release the game, but boy, wasn’t it worth the wait.

Right after we launch it, the game welcomes us with an aesthetic menu. Since there’s nothing to do there, I launch a new game. No intro, not a word of introduction – I’m dragged straight into a nightly forest. A boy enters the frame – looks ten, maybe twelve years old. For now, I can only go right. I have a deja vu – Limbo’s beginning was identical (as were the beginnings of about 96% of other platformers); the atmosphere is similarly dense, but there are no post-processing tricks such as film grain filter. The visuals of Inside are clean, the world is very expressive, its three dimensions are very distinct, as is its depth. At the same time, the kid can only move in two dimensions – left, right, up and down. Jumping onto different crates and boxes is an exception – they seem to be a bit deeper in the background in relation to the boy, who can sometimes move them from place to place. He’s also able to lift them in the latter part of the game when he slightly alters his form. I love the game’s location design, and the main character, who is devoid of any distinct facial features, as if he was a being completely irrelevant to the whole world.

The first ten minutes of the game are shocking. The boy from Limbo, pierced with the leg of a huge spider, or torn apart by a snare trap was nothing compared to the sight of a kid who’s trying to run away just to be shot in the back in the middle of an empty forest. A kid mangled by hounds. A kid pursued by grown-ups who are ready to kill him at any moment. And we haven’t the faintest idea why. The game starts off pretty heavily: people are carried away from the forest in trucks, armed patrols saunter around. Not knowing the context, I was convinced that the small studio decided to provide us with an image of some sort of a ethnic cleansing. Fortunately – for I’m not sure how much of this slaughter of innocent beings I would be able to absorb and not lose my mental soundness – after a couple of minutes, the game gives us the chance to catch a breath and start the proper adventure.

As the story proceeds – presented only by what we see on the screen; there are no dialogues or anything like that – the devs switch from depicting the effects of war (a village full of dead animals), into fantasy. The boy has to break through hallways of sunk men-of-war; when he succeeds, he finds his way into research laboratories, where he sees what the people chasing him are actually about. The story can be treated literally, but it can also be interpreted as a parable, which ends with the transformation of the child – an idea that, to me at least, seems to have been inspired by anime.

The game is controlled by just a single analog stick – responsible for movement – and two buttons – jumping and interaction. Even having such modest controls, the game was able to offer a considerable amount of interesting puzzles. The protagonist does not only have to move items and press different buttons, but also use containers with compressed air. A big portion of the game is spent inside of a bathyscaphe, in which the kid roams the depths of the sea. The riddles aren’t extremely difficult, and even if one of them causes some problems, it will surely give up after a couple of tries.

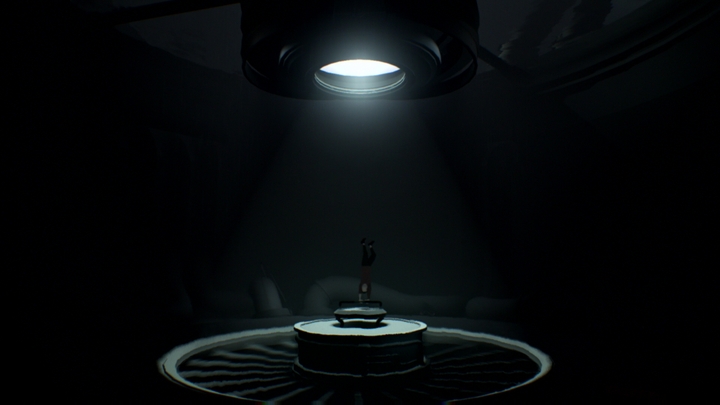

The protagonist is special. The players learn this when the kid connects himself – via his head – to a sort of interface, which allows us to control the mindless characters that can be encountered every once in a while. Those are the people we’ve seen at the beginning being carried away in the trucks. The interface allows us to force them to perform certain tasks. Once or twice the interface stays on the boy’s head when he’s able to move, making all those people follow him with blind submission like mindless zombies.

The Danish studio has worked hard on a realistic rendition of water’s surface and it’s depths. The boy is agood swimmer, but is unable to hold his breath for long (at least at the beginning – this changes later in the game due to some unpleasant events). Under the water, he pulls levers, presses buttons, and avoids a certain unpleasant, uncanny amphibious creature. Meeting it will surely be a thrilling event, and I can guarantee that you will be biting your nails (and not because of frustration).

Finishing Inside takes four, perhaps five hours, and not a minute of this time is wasted. The game is a magnificent piece of code, being a production more mature and overall better than the already great Limbo. Playdead have managed to put more ideas into this game, and certainly were more creative during the development of the game world, which is conspicuous, tangible, and incredibly hostile towards that small, innocent individual chased around for no apparent reason. The moment when the enemies change their attitude towards him will occupy a special place in my memory for a long time. The way the developers managed to express so many emotions with just one move of an animated background character was incredible. Only the best can pull off something like this. Of course, the game reiterates many elements that are known from Limbo, but they have been properly expanded, and – most importantly – they serve the story well. After six years, people still remember Limbo, and something tells me that Inside will be remembered for another decade.

Inside

Inside Review – enthralled by the creators of Limbo

For the last couple of years Playdead have been working hard on a new title, a follow up to the success of Limbo. Inside is the outcome. This is a gloomy journey of a little kid into the world of unethical human experiments.