Gamer Psychology: Why We Rage, and Why It's Ok to

Have you ever screamed in front of a monitor, cursed, tossed a pad, smashed a keyboard? Relax. You can still be normal.

Let's watch a stream of some simple soulslike games tonight. Atmosphere gets denser, the streamer dies fifteenth times in a row, frustration mounts up, crystallized emotions turn into ugly words ("Cock, cock! What else could I call it?!”), until finally, someone on the chat room asks if anyone's recording it.

From this article you will learn:

- what's rage...

- ...and why it's so popular;

- how our brain responds when we face a challenge..

- ...and when we can't brave it;

- when a player experiences catharsis;

- a thing about immature defense mechanisms...

- ...and their far less popular alternatives;

- the appropriate response to transgressing social norms...

- ...and why it's often hilarious nonetheless.

The last seconds before the annihilation of gamepad...

Then all hell breaks loose. The viewer's family life, in particular his relationship with his mother, is subjected to deep scrutiny way back into prenatal times. He is promised that, yes, he will receive the video, with the appropriate dedication, so that his 13-year-old brain can indulge itself by watching it. The bottom line of the streamer's argument is that it's all normal and if someone gets their kicks from swearing, they're probably not the most mature person.

The key question is: is this really normal? And if is, is it desirable? And why are the inadequate emotional responses of a player hundreds, maybe even thousands of miles away, even relevant to us at all?

If you don't understand the introduction, that's fine – it means you don't waste time watching other people play games. The presented situation describes a famous creator, who's getting incredibly wound up playing Dark Souls 2, swearing in pretty inventive words, and when his behavior was ridiculed in the chat, he proceeded to calling the participants of the stream names that even dwarves would be impressed with. The whole situation is now treated rather in terms of an embarrassing joke, though of course – I'm not making excuses.

E-motions

The phenomenon of so-called rage, that is an inadequately vigorous response to frustration in the game, is very deeply rooted in player culture. We like to think of ourselves as civilized, mature, tech-savvy consumers of electronic art, but the predilection for mindless anger is evident in our vocabulary – if you haven't ever ragequit, you're a loser (you should now get angry at me for calling you names, and close the browser, preferably with alt+f4). It seems natural – after all, video games are supposed to cause an emotional response. Delight, joy, relaxation, but also awe, sadness and rage. When games, even these properly designed, are devoid of this kind of emotional charge, they're promptly forgotten, overwhelmed by titles that may be less polished, but resonate with our psyche much more strongly.

What's more, one of the features that distinguishes Interactive entertainment from its other forms, is the manual challenge the player has to overcome. Dealing with a complex problem results in the release of dopamine and endorphins (chemicals that roughly act like opiates) in subcortical structures, causing feelings of satisfaction with progress.

Progress in games is therefore a factor that interacts in a rather sneaky manner with the brain – achieving things completely irrelevant to our survival, such as saving a princess, feels like overcoming genuine obstacles in real life. Even if it eventually turns out that the princess in question is in another castle, we are motivated to return to the pursuit – at the promise of new rewards.

So why do developers strive so hard to design rules that spoil this mechanism? Why are the games that are out for you becoming increasingly popular? Why are they abandoning the formula of a relatively stress-free experience, instead having us endlessly repeat the same levels, learning them by heart? Why play games that feel more frustrating than challenging?

Well, first of all, negative emotions, especially anger, are hugely underrated in western cultures. Expressing anger is a kind of social taboo, stigmatized from an early age: children are taught to be "polite" and listen to their parents. Sometimes, when their needs remain unmet, they manifest it in a more elemental, powerful manner. For this occasion, however, the world invented by adults has a million answers: from humorous, to, much more harmful, unrealistic threats, to completely uncivilized physical violence.

And yet, if any emotion was unnecessary, evolution would have taken it out of our minds millions of years ago, as happened with countless instinctive behaviors. Sadness and a sense of loss is a lesson for people, a regret that needs to be worked through so that they don't repeat the same mistakes. Fear saves lives when we meet a rabies dog in a dark alley. And anger... well, anger motivates more effectively than the synergy of profit, success and video couch from the evening discount at $99.99.

Anger comes when, at a given moment, we cannot achieve our goal, but – unlike resignation – we still believe we can make it. This triggers a stress response and activates the so-called hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to an acceleration of heart rate, an increase in blood pressure and immune system mobilization. While the body's responses are useless when it comes to embracing virtual challenges, they provide direct evidence that anger mobilizes us to fight or flight.

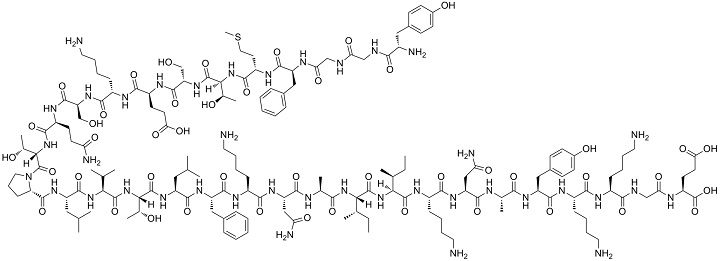

THE HYPOTHALAMIC-PITUITARY-ADRENAL AXIS?

As the name suggests, it's the coupling of three organs: the hypothalamus, the pituitary and the adrenal gland. The first two are parts of the brain, and the adrenal glands are the symmetric glands on the upper poles of the kidneys. The hypothalamus releases hormones that stimulate the pituitary, among other things, and the pituitary stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete corticosteroids, such as cortisol, which is responsible for maintaining high stress response if the threat cannot be immediately neutralized.

Corticosteroids are produced by the cortical part of the adrenal glands. The spinal part is used, among other things, for the release of adrenaline, a substance particularly important in the initial stages of stimulating the body to fight or flight. This is desirable because the adrenal core is stimulated directly by the nervous system, which allows it to react almost immediately, while the cortex needs hormonal stimulation, which takes time – hormones need to enter the bloodstream and from there reach the relevant receptors in the organ itself.

Well-designed games based on frustration always try to make the user aware that they sand a chance. The player usually knows they made a mistake, they lost focus for a moment – that one or two tries more will be enough to finally beat the boss, solve the puzzle. That the princess is in another castle, and if we managed to get through the first one, why couldn't we beat the next?

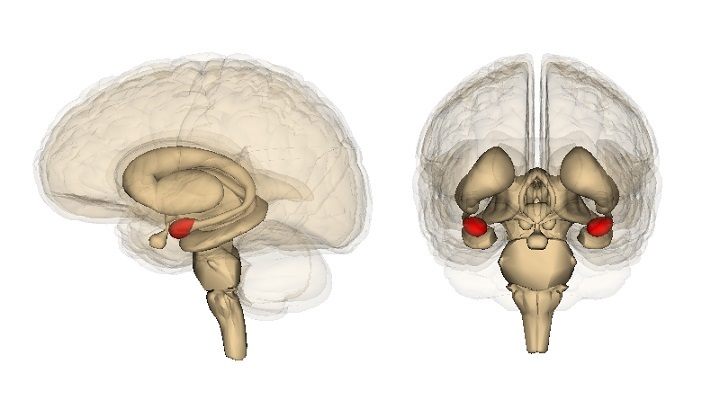

Although the nuanced responses are slightly different, as with reward, when we experience a well-designed failure, the primary, subcortical part of the brain is activated, although this is more about the amygdala than – as it's the case with direct pleasure – the semiplegic nucleus. Dopamine levels continue to rise – because it is a relay of expectation and motivation.

The amygdala is commonly associated with the generation of negative emotions and is identified with the so-called punishment system. But this is a harming simplification – the amygdala is much more vital than that – it is a sort of emotion command center.

By connecting to sensory centers, it can classify the circumstances we're in before we even consciously know it, and transmit information about it (accordingly tinged emotionally) to the hippocampus. There, a search of procedural memory (a hellishly complex, still mysterious process) takes place and coping strategies are selected.

All of this essentially happens without the engagement of consciousness. Conscious analysis of stimuli is triggered only later and involves inhibition and possible modification or uncritical initiation of the instinctive response. As you can see, most of the emotional dilemmas are resolved independently of what we commonly consider our will.

On the neurobiological side, therefore, facing frustrating challenges is not that different from stress-free pushing through a game like a casual after overdosing micropayments.

Moving to a more abstract level, one should mention the catharsis – a phenomenon known since the ancient times – and move on to the right subject of consideration: rage per se; not simply anger.