On Moral Choices in Video Games - With Developers of Frostpunk and This War of Mine

In an industry that has a bee in the bonnet about "hard moral choices" for a good few years now, few developers can get this difficult element right. But there's at least one studio you could learn from.

- On Moral Choices in Video Games - With Developers of Frostpunk and This War of Mine

- A shard of ice instead of a heart

- Forced evil

Darkest Dungeon is a monstrously tiring game for me. The constant tension, the relentlessly rising stress indicators, the realization that each room you enter might hold a horror that would first possess the minds of the warriors (I had already invested so much time and effort in them) and then devour them alive. I never made it to the end – although I was absorbed by the atmosphere and could manage the team quite well, the prospect of losing one of my most loyal soldiers at certain stages was too much to take. Sending my trusted charges to potential doom and watching them inevitably succumb to madness was, at some point, beginning to overwhelm me.

However, I recently read an interesting article that argued that Darkest Dungeon, with all its randomness and unforgiving mechanics, can be really simple. For there is a resource that is always in abundance in the town we manage: heroes. No matter how many people we lose in the fight against the monsters from the worst nightmares, there will be new ones in the tavern, willing to take on risky assignments. There's nothing stopping you from sending more newbies to the dungeons, forcing them to fight in the dark (which results in better treasures), and discarding them as soon as the horrific experience breaks their psyche.

In the meantime, we can always train a few fighters for the toughest challenges. No one will judge us for it, the townspeople will not demand that we stop this monstrosity. The only price to pay for this approach is watching the minds of legions of our warriors struggle with horrible nightmares and ultimately succumb to them – time and time again. And again, and again.

This article would have been much less extensive it weren't for the time taken by the developers from 11 bit studios to explain the mechanics of the moral issues in their games. My sincere thanks go to Maciej Sulecki and Jakub Stokalski for their substantive input and for sharing the behind-the-scenes of the creation of This War of Mine and Frostpunk. Konrad Adamczewski deserves huge thanks as well for his patience in answering the avalanche of my emails and getting me in touch with his colleagues.

Morality at your fingertips

I have a problem with morality tests in games. In essence, it's the fact that most of the difficult, ambiguous choices that modern adventure games and RPGs offer could just as easily be featured in Netflix's next experimental interactive film, something along the lines of Bandersnatch. These decisions are somewhat separated from the core gameplay, are presented in the form of QTEs or dialogues, and have us choose one of the presented actions. They take the steering wheel from us and ask if we prefer to hit the car in front of us, the pedestrian to the right, or plunge head-on into the truck coming from the opposite lane – and when they hand me back the controls, they say: "Well, it was your choice after all, so deal with the consequences."

What I abhor even more are the systems that give us morality meters, quantifying all our choices. You know, the honor meter from Red Dead Redemption for example, which tried to convince me that I could redeem all my murders and sadism by saying "Hello" to old ladies enough times. With all due respect to Rockstar, but I have a hard time lending any credibility to an honor system in a game, where tying up a person and laying them on the tracks to watch them get smashed by a train is rewarded with an achievement.

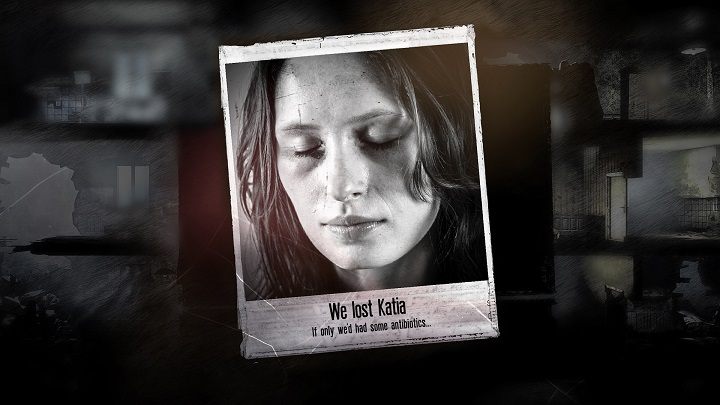

Do you want to know which game's morality system I did find credible, even though it proposed some very difficult choices? It was This War of Mine, a 2014 survival game in which the developers, the Warsaw-based 11 bit studio, put us in control of a group of civilians during an undefined, armed conflict. It was a game that deliberately let go of morality meters and different-colored circles with dialog options.

"At a fairly early stage of development, we assumed that if we're making such a grim game, based on real events and depicting a humanitarian crisis, we don't want to judge the player," says Maciej Sulecki, one of the designers.

That may well be true. I am judged by other characters in the game. But – most importantly – I judge myself.

Our personal morality meter

The so-called "moral choices" in This War of Mine don't consist of clicking one option and watching the consequences in a cut scene – it's a whole process.

"It's very easy to click "yes" or "no" on a simple board," explains Maciek. "But when you decide to rob someone, you always have time to think twice about it, take a step back, to let go.

I know all too well what he means.

On one of my first approaches, I decided to search the home of a certain elderly couple in hopes of finding medicine for a sick companion. The old men discovered me and began begging me to leave them the med kit because they wouldn't be able to survive without it. I left, empty-handed, and went to the military hospital instead. On the spot, I quickly realized that stealing even a single bandage would require me to take enormous risks, cunning and luck. If the soldiers discover me, I'll only have more wounded to tend to. I only took a few ordinary materials lying near the entrance, escaped, and returned to the old couple's house the next night. They still asked me to leave the drugs for them, but this time, I didn't budge. I had a choice between my people and two strangers – and I chose my people. And then I turned the game off and didn't come back to it for a good week.

Developers from 11 bit studio did not initially plan to create a production so strongly testing our morality.

"We thought of This War of Mine as a game depicting the civilian's experience in war, and that naturally entails difficult decisions. We took these dilemmas for granted in a situation of conflict, danger and resource problems," explains Maciek.

In fact, the game feels as if the moral choices stem out naturally, along with reading reports and accounts, and watching documentaries. This is because the creators have given up on characters with strong personalities, on heart-breaking cut scenes, on a carefully plotted story. In This War of Mine, our path and the extent of what we can do in the name of survival are determined solely by ourselves. Characters react to our actions, of course – but some may not have the slightest issue justifying the murder if it served the group.

The hackneyed slogan about a world in which no choice is black-or-white, often used by contemporary productions in advertisements, finds an entirely different meaning here. In This War of Mine, decisions aren't black, nor white, in fact – they aren't even gray until they're digested by the players. Those who don't empathize with the reality presented by 11 Bit may not even realize that the game is meant to put their values to the test.

"The morality system is delegated into the player's head. We must answer ourselves whether it was worth it, whether we could have done something better, whether we hurt someone," says Maciej Sulecki.