The pink eighties. How Hideo Kojima Brought Hollywood to Video Games?

- How Hideo Kojima Brought Hollywood to Video Games?

- The pink eighties

- Somebody stop me, or I'll end this series!!!

- Trouble in Paradise

- New beginnings

The pink eighties

Talking about his origins and the difficult beginnings in the video game industry, Kojima recalled:

The industry was full of dropouts, people who felt like games offered them another chance. I met many people in that same situation; we bonded together through that in some sense.

Hideo Kojima in an interview for The Guardian

This, however, was only one side of the coin. The other was the initial disappointment and frustration. The young enthusiast had ambitions of working on the latest products for the Nintendo Entertainment System, but instead, he was appointed to work on titles for the much less exciting MSX computers and arcade machines. No one took him too seriously, too, as he wasn't able to program. In those days, the rule of the day was "everyone does everything," so a developer who could neither write a few lines of code, nor create a few sprites for the graphics department wasn't considered particularly valuable.

His ideas and suggestions often went by unnoticed, and the first game created according to his original design, the platformer Lost Warld, was binned by the decision of Konami's management before it even saw the light of the day.

In 1987, Kojima was entrusted with a new, unassuming project called Metal Gear. The development of that game was rather sluggish – the limited capabilities of the MSX2, the target platform of the game, made creating a decent combat system nearly impossible. The young developer opted for an original solution. Inspired by the movie The Big Escape, he decided to shift the center of gravity of the game. Instead of fighting, he would focus on avoiding enemies. And so, one of the first representatives of the stealth genre was born... and was completely unsuccessful. At least, not immediately, and not thanks to Kojima.

Because Konami decided to get Metal Gear to the NES, and commissioned the creation of the port to Masahiro Ueno, who introduced numerous changes. He made the game easier, deleted the last opponent (that is, the title Metal Gear). Because of the console's technical shortcomings, this version looked less impressive in technological terms, and the poor translation was damaging to the storyline. Kojima openly criticized this version of his game over the years (which is quite rare in the Japanese culture), but paradoxically, it was the Nintendo Entertainment System edition that enjoyed financial success in the West and convinced Konami to continue the series.

The birth of a star – directed by Hideo Kojima

After Metal Gear, Kojima created Snatcher for MSX2 and NEC-PC8801 – that was a cyberpunk adventure game about a detective, who faced the threat of cyborgs killing people and seizing their identity, Philip-Dick style. Although, because of time constraints, Kojima's team was forced to shrink the game considerably, the storyline conclusion was greatly appreciated by the critics. Praises were sung about the mature storyline, an unprecedented level of cinematography, the graphics, the voice acting (and Snatcher really had great music and dialogs) – virtually every element relevant in a story-driven adventure game. But still, Kojima was one factor short of a real success – the sales were unremarkable. Snatcher sold poorly, and today it is remembered mostly by Kojima 's biggest fans.

Metal Gear 2 fared better. Developed in 1990 and released only in Japan for the MSX2, the sequel was superior to the original in all respects... and was created only because a little earlier, Konami released Snake's Revenge on Western markets, a different sequel to Metal Gear, in production of which Kojima wasn't involved. The designer did not like that the decision to continue the series was taken without his knowledge, and so he made his own sequel.

This resulted in Metal Gear actually getting two sequels, which can be a bit perplexing – the official one, Metal Gear II, created by Kojima and for a long time available only in Japan, and its lesser sibling, released outside Japan, the non-canonical Snake's Revenge. What's interesting is how much Hideo Kojima openly criticized the NES port of the first Metal Gear, over which he had no custody, since Snake's Revenge is considered a pretty good game overall.

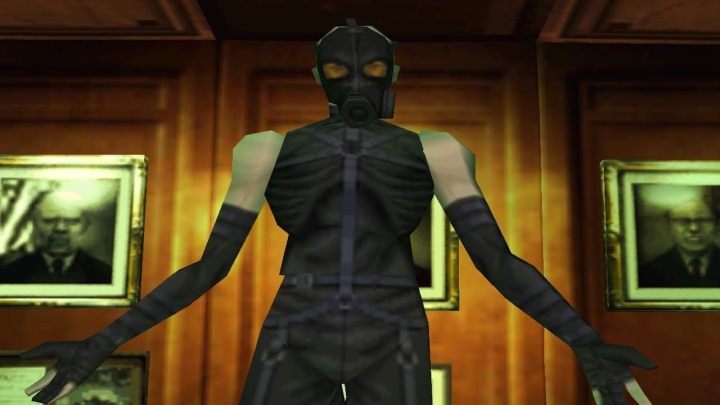

In the years that followed, Kojima worked on several games, but of all these, there's one that really counts. Metal Gear Solid. The next game in the series was created for PlayStation, and introduced the third dimension. Kojima finally got the technology that warranted full realization of his cinematic aspirations, which resulted in a title that was as much a stealth game as it was an interactive movie – full of cut-scenes, cinematic camera work and dialogues.

Gaming hadn't seen anything like that before: fresh ideas were accompanied by graphics that really gave the first PlayStation a run for the money; the polished mechanics and engaging, multi-thread plot made everyone go crazy about Metal Gear Solid – critics and players alike. The game became an instant classic, and is venerated to this day, with the man who created it becoming an industrial celebrity to equal Sid Meyer or John Romero.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Did you ever notice that while in the first Metal Gear Solid the dialogues were pretty much toned-down and quite reasonable, in MGS2 they become much more off-beat, sometimes even borderline unintelligible? In Metal Gear Solid 4, for example, we can hear a flower saying something along the lines of "If you're not a prisoner of fate, go, fulfill your destiny." Underneath this radical change in quality and style of dialogue, there's a story of a translator, Jeremy Blaustein.

In 1997, Blaustein was given the gigantic task of translating Metal Gear Solid from Japanese into English. For the completion of the task that would normally require a full team of experienced linguists, Jeremy had just six months. He took the challenge, giving it his best shot. To get a better feeling of the military jargon, he would read books from a former Navy Seal, Richard Marcinko, and watched war movies.

In the end, he decided that he was ready and able to adequately convey the spirit of what Kojima wanted to say. At the same time, he adjusted for the cultural differences and was not afraid to bring the source material closer to Western audiences or modify the meaning so it was more easily understood. For example, when the original phrase read: "I used my powers for the first time to help someone. It's odd... such a... nostalgic feeling," Blaustein changed the line to: "This is the first time I've used my powers to help someone. This is odd... and... a very... pleasantly... feeling." He also coined the name "codec" – Kojima simply referred to the wireless radio used by the protagonist as "wireless" wireless.)

Although it was an enormous undertaking, he managed to meet the deadline. His work was widely appreciated – also by Kojima. Things changed, however, when, upon closer scrutiny, it was discovered that Blaustein approached some of Kojima 's messages with, well, too much liberty. Knowing only one language, Kojima – perhaps not quite aware that literal translation doesn't work most of the time – was quite repulsed by the notion of anyone tempering with his work.

As a result, Konami never offered Blaustein the job of translating a Metal Gear game again, and the subsequent translations were supervised much more closely to make sure the translators didn't deviate too much from the original. The peculiar dialogues sometimes referred to as "Kojimisms" became a hallmark of the series, and we expect them to be rather abundant in Death Stranding. Some love them, others laugh at them. Unfortunately, there's no way to tell whether Jeremy Blaustein's translations would work out better in later MGS games.

You can learn the entire story of Blaustein's translations here.