The 10th Anniversary of BioShock Infinite, Game That Boldly Deconstruced American Exceptionalism

There is always a lighthouse, there's always a man, there's always a city. And there's always the ideology that BioShock is trying to deconstruct. In Infinite, it was about a particularly sensitive issue: the American sense of uniqueness against the whole world.

3

When ten years ago, we were approaching the release of Bioshock Infinite, many of us wondered weather after the decent, but derivative BioShock 2, the game would turn out another bag of disappointments – the bar that was set incredibly high by Irrational Games with the phenomenal original, which is still considered one of pinnacles of interactive entertainment. Not everyone seemed thrilled with the decision to ascent the setting from the grim and grimey depths of the ocean floor all the way into the candy-colored, floating balloon city. But there was another discussion going on, and it went far beyond questioning the design decisions. Ken Levine, BioShock Infinite's lead writer and creative director, was facing accusations of... anti-Americanism.

You wouldn't tell by the game's first minutes: Columbia seems a proof of American ingenuity and entrepreneurship. The city is elevated miles above the surface, the streets are clean, houses are well-kept, it all looks like Disneyland with a vibe of some grand celebration. Of course, we can sense that something is off; associations with religious cults soon pop up, and historical figures being officially declared saints seems an act of trumpery at best. Other than that, Columbia seems to function flawlessly, and its inhabitants seem to feel as cozy as jelly in a peanut butter sandwich.

But then we get to a lottery, where the prize is literally triggering the lynching of an interracial couple, and the dirty truth becomes revealed like poop from underneath melting snow.

Land of the free, home of the brave

Now I never bought all these allegations of BioShock Infinite's anti-American sentiment; conversely, I had a very clear picture of the reasoning behind the game's main concept. As in the previous parts, Levine and his team looked at a particular ideology and speculated what effect it would have if a society turned it to eleven. But you know, the first and second installments played it fairly safe – they criticized objectivism and collectivism, respectively, so it was easy to dismiss that as criticizing "the commies" or another gross simplification like that. Meanwhile, BioShock Infinite hit right in the gut: it dared to examine the myth of American exceptionalism.

The myth itself, as any myth out there, has its justification. The United States is a phenomenon in several respects: a "nation 2.0," settled across the Atlantic, which in the fire of revolution forged the longest, uninterrupted, more or less democratic experiment in history. Of course, we fast-forward a few centuries and end up invading multiple nations across the world, acting as "global police" in the best case, and securing our profits and greedy influence with military might in the worst. The history of the USA, however unique and often inspiring, stands on ethical quicksand – just like the city floating in the clouds.

The belief in American exceptionalism was first expressed by the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville in the first half of the 19th century. In the modern definition, it consists of values such as freedom, egalitarianism, individualism, republicanism, democracy and a passion for laissez-faire economy. Interestingly, the term was popularized back in the 1920s by... the American communists (claiming that the history of the United States, due to the lack of a clear class division, allowed its society to escape the framework of Marx' theory of historical materialism). In the following decades, politicians from both sides of the aisle referenced it: from JFK, through Reagan, up to Obama.

BioShock Infinite tackled this idea by portraying a reality, where these principles were taken to the extreme. The very concept of a floating metropolis shows that. In American politics, the United States is often referred to as the "City Upon a Hill." Columbia was founded as the embodiment of this idea: it was intended to fly around the world and propagate these national values. And all was dandy, until in 1902, without a permission from Capitol, Columbia intervened in China's Boxer Rebellion, razing Beijing to the ground in retaliation for taking American citizens hostage – and when condemned by the federal government, the city declared secession and vanished into the clouds.

The builders of the metropolis, however, didn't turn their backs on their identity. Not only that – they went all-out nationalist, pushing the idea far beyond pride or patriotism. In Columbia, America is religion. As we arrive in the city, we're greeted by statues of the three Founding Fathers dressed in togas, bringing attributes of power to ordinary people. Prayers are offered to one of them, George Washington: "He, who crossed the Delaware with flaming sword and wings of angels." The founder of Columbia, Zachariah Comstock, is the heir of the nearly divine wisdom of the progenitors of the American nation: they're the holy trinity, and he is a prophet, while his daughter (conceived in unclear circumstances) is the lamb-savior. That sums up the religious references.

The point is that such a pious view of the origins of the United States is not far from the actualy perception of it in the USA even today. The Constitution, signed in 1789, and the Bill of Rights introduced shortly thereafter, are still presented as almost perfect documents that require only minor corrections. When discussing changes to the existing wording of ammendments (today primarily the second ammendment), one the first arguments is whether the new legislation would not contradict the ideals of the Founding Fathers. They, in turn, are treated as models of virtues of all kinds; our moral compasses. I mean, there's not many people so influencial that someone decided to turn a mountain into their monument.

The plantator's handbook

In Rushmore, alongside Jefferson and Washington, we will also find Theodore Roosevelt – who would have just begun his first presidency at the time of Columbia's secession – as well as the good, old and austere Abraham Lincoln. But the latter doesn't get such affection from the citizens and masters of the world of BioShock Infinite. On the contrary: in one of the voxophones, Zacharias Comstock calls him the Great Apostate, who brought nothing but death and destruction to his nation. At the headquarters of the Brotherhood of the Raven, another unsubtle reference, this time to the racist-terrorist organization Ku Klux Klan, Lincoln is portrayed as the embodiment of the devil, while his killer, John Wilkes Booth, can boast a few monuments and paintings. Why does Columbia hate the 16th president of the United States so much? We have no rewards for answering this question.

Of course, it all comes down to the role that Abraham Lincoln played in abolishing slavery. The early 20th century, i.e. when BioShock Infinite is set, racial segregation was in full swing with Jim Crow laws enacted, Ku Klux Klan going through a revival, and literally thousands of lynchings happening around the nation. And Columbia doesn't do much to change that. The local equivalent of the Klan is headquartered right in the city center, lynchings are a fete attraction, and equality campaigns are only prepared in secrecy. Comstock himself compares human beings to dogs and dabbles in phrenology – a pseudoscience that was supposed to give racism an academic grounding by studying the dimensions of the skull. He uses the same rethoric as the apologists of the Confederacy, who undermined the legitimacy of the abolitionist cause.

What exactly was the “Great Emancipator” emancipating the Negro from? From his daily bread. From the nobility of honest work. From wealthy patrons who sponsored them from cradle to grave. From clothing and shelter. And what have they done with their freedom? Why, go to Finkton, and you shall find out. No animal is born free, except the white man. And it is our burden to care for the rest of creation.

Zachariah Comstock's laying it on thicc

But prejudice doesn't end with racism here. Another discriminated group were the Irish, considered lustful drunks and as such, forced to use separate restrooms. Their purpose is to remain unseen, not to spoil the vision of a perfectly clean and white city. They do the hard physical work and receive starvation wage for it that doesn't even let them get out of the slums. And just like African Americans, they become the first recruits of the revolutionary organization Vox Populi.

In Columbia's propaganda machine, Vox Populi is the biggest – right next to the "False Shepherd," who quickly turns out to be us – enemy of the powers that be. The organization is composed primarily of marginalized groups: immigrants, minorities, manual workers, all demanding better living conditions and fair pay. In BioShock Infinite, we're reminded of the long and bloody history of suppression of protests, and other anti-union activities. The turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, as a crucial time in the creation of modern workforce, was particularly brutal in this respect – back then, military and private agencies, such as Pinkerton, were used to suppress protests. Interestingly, Booker de Witt, the protagonist of BioShock Infinite, was both in the army and in the Pinkerton Agency, and even participated in quenching strikes with violence.

If facts don't support the theory...

However, while some minorities were allowed to live and work in Columbia – even if in inhumane conditions – other minorities were excluded even from that "privilege," and indeed, cracking worker resistance along racial lines and thus creating friction among people, in whose best interest it is to remain united, is one of the oldest strategies that power and capital maintain the status quo. Asians were most likely expelled shortly after the razing of Beijing. At the very beginning, the pastor who baptizes the protagonist mentions that Comstock chased away the "vipers of the Orient" from the city – probably talking about the people who built the city in the first place. Native Americans aren't mentioned as often, and the game implies that the prophet himself is partly Native American. However, both groups play a key role in one of BioShock Infinite's most important themes: the mythologizing of Columbia's, and by extension, of the United States' history.

In each of these cases, Irrational Games reminds us that American history has been – like the history of almost every nation – a trail of exploitation and injustice marked by suffering, viewed through a set of lenses that allows the creation of a glorious image and evokes a sense of patriotic pride. Nowhere is this more evident than in the depiction of the bombing of Beijing and the "battle" at Wounded Knee. The latter was actually more of a massacre, with the US Army murdering more than 150 Lakota people (including women and children) who were fleeing retaliation. However, this isn't the case at Columbia's Hall of Heroes: Native Americans are depicted as crazed savages, treacherous, murdering the defenseless.

With hue and cry, with hatchet red, they danced amongst our noble dead.

But when our soldiers took the field, the savage horde could only yield.

Motorized Patriot once again

The fictitious bombing of Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion received a similar treatment. In the BioShock Infinite lore, Columbia razes the capital to the ground in retaliation for taking Americans hostage. The Hall of Heroes presents this event as justice delivered for the insidious Chinese, shown in a way resembling vampires: with sharp claws and animal fangs.

'Twas yellow skin and slanted eyes that did betray us with their lies.

Until they crossed the righteous path of our Prophet's holy wrath.

Motorized Patriot once again

Maybe it's a stretch, but the theme of Beijing's obliteration has always reminded me of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which even many military leaders of the time believed were not so much a means of forcing Japan to surrender and end the Pacific War as a show of US military might against the Soviet Union – and today, their use is increasingly considered a war crime of shocking proportions. But even if it is indeed a stretch, trying to wash a slaughter of indigenous tribes with noble ideals, destroying an entire city, or enslaving people, are elements of BioShock Infinite that undoubtedly criticize the mythologization of history that people can experience in USA, and beyond under nationalist or supremacist ideologies. A mythologization is absolutely necessary to be able to put oneself in the role of a moral compass, especially on international scale (another mandatory thing would be capital and probably aircraft carriers).

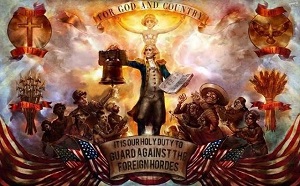

In its critique of the idealized vision of the United States' history, BioShock Infinite is by no means subtle: the logo itself consists of a torn American flag, and the propaganda posters strike with slogans straight from the most inhumane authoritarian systems. But for some, apparently, even this, rather blunt approach, was still too velied. In December 2013, the National Liberty Federation, a group inspired by the conservative-libertarian Tea Party, shared on its Facebook profile one of the posters from the game. It depicted George Washington holding tablets with the Ten Commandments, and fighting off caricatures of Irish, Arab, Asian and African characters. The inscription read: "For God and Country – It Is Our Holy Duty To Guard Against The Foreign Hordes." Well, at least they were being honest.

Vex everyone, spare no one

There's a bit of a universal message in this, because after all, every nation has tried or still tries to bleach the dark pages of their history. America, however, seems to be a special case in this regard – having been the perhaps the only true winner of WW2, it became a global superpower and a pop-culture powerhouse that got the unique chance to promote the washed ideas about itself to the whole world. The States always overcame their problems and always ended up on the right side of history. BioShock Infinite sprinkled salt on wounds that seemed long healed: it reminded of the nasty history of racism, jingoism and religious fanaticism that still takes its toll in the public debate, with the cracks dividing the society being as wide as ever. Ken Levine, the game's director, was well aware of the reaction he would get.

When I started working on this game, relatives of mine were very offended, because they thought it was an attack on the Tea Party. Specifically an attack on the Tea Party, which they were very active in. Then, when we sort of exposed the Vox Populi people, I saw a lot more left-leaning websites being like, “This is trying to tear down the labor movement!” I remember that I saw postings, unfortunately, on a white supremacist website, Stormfront, where people literally said, “The Jew Ken Levine is making a white-person-killing simulator.” And BioShock had the same thing, where you had Objectivists being infuriated by it, and people more on the left thinking that it was a love letter to Objectivism. I think these games are a bit of a Rorschach for people. It's usually a negative Rorschach. It pisses them off, you know?"

Ken Levine in an interview with PC Gamer, December 2012

Perhaps there's a grain of truth in this, and art, to be truly valuable, must be uncomfortable.

3

Author: Jakub Mirowski

Associated with Gamepressure.com since 2012: he worked in news, editorials, columns, technology, and tvgry departments. Currently specializes in ambitious topics. Wrote both reviews of three installments of the FIFA series, and an article about a low-tech African refrigerator. Apart from GRYOnline.pl, his articles on refugees, migration, and climate change were published in, among others, Krytyka Polityczna, OKO.press, and Nowa Europa Wschodnia. When it comes to games, his scope of interest is a bit more narrow and is limited to whatever FromSoftware throws out, the more intriguing indie games and party-type titles.

Latest News

- End of remote work and 60 hours a week. Demo of Naughty Dog's new game was born amid a crunch atmosphere

- She's the new Lara Croft, but she still lives in fear. Trauma after Perfect Dark changed the actress' approach to the industry

- „A lot has become lost in translation.” Swen Vincke suggests that the scandal surrounding Divinity is a big misunderstanding

- Stuck in development limbo for years, ARK 2 is now planned for 2028

- Few people know about it, but it's an RPG mixing Dark Souls and NieR that has received excellent reviews on Steam, and its first DLC will be released soon