How I Survived Another Summer. About Games That Are (Not) Afraid of Cold

At the end of the summer, I would like to pay tribute to the productions that for the past few years have allowed me to survive the increasingly unbearable heat, and at the same time reflect on why games – unlike other cultural artifacts – shun cold so much.

4

In The Long Dark, a game I've been launching regularly for five years as soon as the very first signs of summer heat appear, I'm not the only main character. Maybe I do singlehandedly hunt animals, collect tons of wood and try to map the area with no success with a piece of charcoal and some paper, but I am by no means alone.

What accompanies me at all times is the cold: I hear it howl in the gusts of wind pushing against the walls of my shelter; I see it in the fog, heavily resting upon the lake covered in ice; I feel it in the weight of my clothes slowing down my steps. It's the Cold with a capital C, not just a chilly weather that requires turning the heater on and wearing a light sweater; it's the actual white death. I won't admit to myself – let alone to you – that I am completely terrified of extreme cold, which stiffens the muscles and turns skin blue. I always play The Long Dark with a blanket and hot tea at hand, just in case.

It's a game that fits the long list of works of art that tap into the huge reservoir of our innate frigophobia and does it in a dignified way, too. The Thing by John Carpenter, Revenant, The Day After Tomorrow in movies; Dan Simmons' The Terror and probably half of Jack London's written output in books; The North Water on TV; only video game developers seem to ignore how frightening icy climates actually are. In interactive entertainment, winter is mainly a backdrop for some individual stages, occasionally the entire game, but temperature is rarely a core statistic.

In the great white nothingness, death is slow

No matter how much I regret it, I am not surprised by this. The frosty landscapes are breathtaking, the stories of surviving in the taiga or tundra are fascinating testimonies of human determination, but the mere fight against cold is, in theory, nothing exciting. Snow slows you down, it's heavy, it sticks to clothes and constrains movements. Even our metabolism slows down along prolonged exposure to cold. It also takes a long time before the cold starts to do serious harm: hypothermia becomes a serious threat only when the body temperature drops by a good few degrees, dangerous frostbite is also a matter of at least several dozen minutes of exposure.

All of this has an impact on the gameplay. For example, Frostpunk cannot really be played in the long run without speeding up the time so that the hours pass in a matter of seconds. But the first contact with the game – the lines of miners making their way through waist-deep snow and the mighty wind rolling over the frozen wasteland – all at a snail's pace – immediately telegraph the desperation of our circumstances. In the prologue of Red Dead Redemption 2, the cold is used in a similar manner: at the very beginning of Rockstar's masterpiece, Dutch van der Linde's gang seems to be worried primarily about the botched Blackwater heist, but its desperation is ever so greater because of the raging blizzard. The wagons ponderously break through frosty mountain trails, it is impossible tell how far behind the law is in the thick snowstorm, and the severe cold makes it impossible to properly treat injured members of the gang. You don't need any dramatic dialogues to see how hard things are right then and there.

True stories of survival – or perishing – in extreme cold are abundant. One of the most impressive ones is the experience of Richard Byrd, an American explorer, who spent five months alone in a small cabin at the North Pole in 1934. He was supposed to conduct meteorological observations and obtain various measurements, but he had to face a much more difficult challenge. As he later admitted "Perhaps the desire was also in my mind to try a more rigorous existence than any I had known."

Interestingly, the cold had threatened his life only once – when the hatch of the shelter froze during one of Byrd's forays outside. Poor ventilation turned out to be much more dangerous, meaning the cabin would begin to fill with carbon monoxide each time the stove was lit. Left completely alone, the American had to decide regularly whether he preferred to risk suffocation or frostbite; he considered suicide at least once. Ultimately, however, he was rescued and a few years later returned to Antarctica on a government-backed research expedition.

Meat and bones

Cold as an element of mechanics rarely appears in games, because there is no room for it in the so-called "fantasy of strength." When engaging with interactive entertainment, we want to be assassins, detectives, samurais, cybernetically enhanced gangsters; in essence – someone we (most likely) are not every day, someone who does things we cannot do ourselves. Cold, in turn, exposes all our weaknesses and reminds us that in extreme conditions, we're little more than walking bags of bones and muscles, extremely fragile and susceptible to the elements. The Long Dark or Frostpunk are the antithesis of the fantasy of strength: these games throw us into hostile conditions and start killing us almost from the first seconds.

The amount of time for which we can chase away the specter of death is only a matter of player's choices and luck.

"Most times when you die in The Long Dark, it's an outcome of decisions you made days or weeks before. Apart from if you fall from a great height, or get ravaged by wildlife, your survival, or your demise, are a constant open question. This is core to the design philosophy behind the game. Things like Hypothermia and Frostbite are warnings that things are going badly for you. Generally, the solutions are obvious. Achieving those solutions, on the other hand, often isn't."

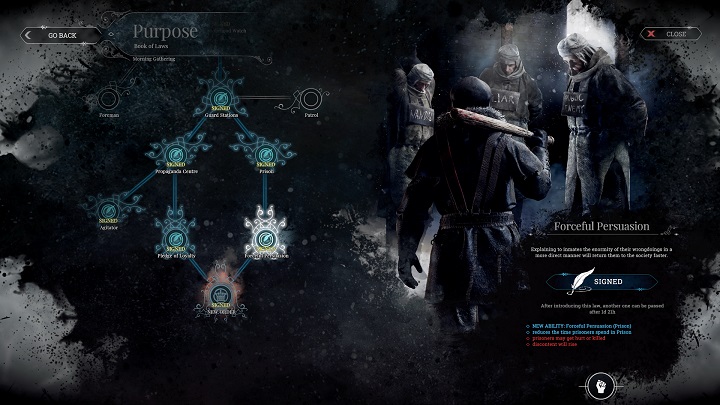

The feeling of helplessness against the environment and the awareness of life fading away with every minute in the cold weather creates an incredibly suggestive experience in which it is easy to succumb to desperation. This is especially clear in Frostpunk, where drastic measures need to be taken as temperatures are getting increasingly extreme. Send kids to the mine to get more coal to power the heat generator? Give up the treatment of frostbitten limbs to save necessary resources? Bury the bodies of the dead or leave them in the cold so that they can be used in the event of a hunger crisis? The game from 11bit studio pushes us to enact inhumane, totalitarian laws that are completely contrary to our convictions because it constantly reminds us that we're the last bastion of humanity – and freezing to death.

Naturally, this is just my impression, but the oppressive atmosphere of a brutal winter in games has remarkable power to bring out the worst tendencies of players. In Frostpunk, the cold makes us ruthless beyond cruelty. In The Long Dark, it induces risky, sometimes downright stupid behaviors. I have died there dozens of times precisely because I decided to jump off a high rock ledge, walk across the lake covered with thin ice, or risk a fight with a wolf – fearful of quickly progressing hypothermia. Cold as a key part of the game's systems not only makes us aware of human vulnerability to weather conditions or temperature, but also emphasizes those aspects of our character that, in extreme situations, would probably lead us to death.

Here, of course, I must point out – just like Hinterland studio does – that The Long Dark isn't a realistic survival simulator.

In fact, despite speaking with a few of them, we didn't end up using any survival experts in the end. We did our own research, conferred with friends and colleagues who were mountain guides and very experienced outdoors-people, and used that information to inform decisions we made for the benefit of the game. But in the end, gameplay always came first, and we didn't let ourselves get overly distracted by trying to recreate or simulate wilderness survival. Most of what is in The Long Dark is just logical, and it makes sense to anyone on an intuitive level. You don't need to be a survival expert to be able to figure out what you should do next in this context.

Raphael van Lierop, founder of the Hinterland studio.

If the mechanics of cold are difficult to realistically recreate in video games, it seems almost impossible to do it with heat. Which, of course, doesn't mean no one has tried. The closest, "hot" counterpart of The Long Dark would be Arid, a free survival game released last year, in which our worst enemy are extreme temperatures, thirst, lack of shelter, and sandstorms. It doesn't have as much content as Hinterland's game, and some of its systems make it even more ruthless, but it's still a pretty interesting game – this time for wintertime.

Many systems in this production are interlaced, which means that even if the developers are careful not to make their game a guidebook to survival in the wild, it's easy to get full immersion. Cold wind makes the temperature much more severe, is able to put out a flimsy fire, carries our smell, exposing us to predators; not only does hypothermia drain our vitality, it also slows down our movement and makes it harder to aim. Frost affects absolutely everything and sometimes it is difficult to hide from it even in closed rooms. At times in The Long Dark, I felt like in a horror movie in which the killer harassing me doesn't allow more than a moment of respite.

A prettier apocalypse

In Frostpunk, the oppressiveness of the environment is additionally enhanced through the visual setting. When the game shows a bigger chunk of the map for a moment (when we send out scouts), we quickly realize that our shelter is probably the only place that is not frozen to stone within hundreds of miles. The city we are trying to run starkly contrasts with the deadly, all-consuming whiteness: black, gray and brown, lit by the orange flames. The settlement we're building in Frostpunk is not an architectural masterpiece. It's a pile of improvised buildings and tents crammed together as tightly as possible, as long as they get at least some heat from the generator; it's a Dickensian nightmare which almost oozes the smell of smoke and the sour scent of crowded slums. Frost pushes the aesthetics to the bottom of the priority list – once again, it's only survival that counts.

The Long Dark took a completely different direction.

I knew that I didn't want yet another grim, colorless post-apocalyptic setting (which were so popular back when we were first working on The Long Dark), and so to stand out, we went in a different direction. I appreciated the contrast between a deadly environment that is slowly killing you with every second that passes, and also the magnificent beauty of the natural world, and to render it faithfully felt like we needed to lean into fine art.

Raphael van Lierop, founder of the Hinterland studio.

Of course, The Long Dark has moments when the visuals are tuned-down – fog laying on a frozen lake or a night blizzard limiting visibility to just a few meters – overall, however, the game is visually breathtaking. Sunsets burst with a fiery of deceptively warm colors, green auroras illuminate the night sky, peaks on the horizon comb the multicolored clouds. The brutality of the conditions is mostly conveyed by the audio setting.

" You can hear the sound of snow crunching under your feet, and that sound changes the colder the temperature is, as anyone who's experienced cold winters knows. Same thing with how your clothing sounds as you move. The colder it is, the stiffer and creakier the sound of the nylon jacket and pair of snow pants becomes. There are moments when your survivor comments on their state, and they become colder, they will comment on that. Sometimes you'll hear shivering and teeth chattering, as you become increasingly cold.”

To some extent, The Long Dark is a reality check for the player, who's probably used to treating the natural environment in countless high-budget productions as their own private sandbox (similarly to real life, actually). This is one of the few titles that require you to carefully consider the surroundings and constantly react to the changing temperature, wind direction or reduced visibility. It teaches respect, even if it's sometimes an extremely laborious process. Its creators do not hide that they want this respect to go beyond the scope of interactive entertainment.

"Growing up in Canada, the wilderness is all around us. I've personally had many various experiences being in the wilderness, from simple camping to more rigorous excursions in the far northern wilderness, and we have some die-hard hikers, climbers, and general outdoors-loving folks on this team. But really, to live in Canada is to feel the presence of mother nature around you at all times. It's beautiful, and wild; it informs so much of our identity. We're also becoming more mindful of our often harmful impact, and the steps we can take to do more to preserve and protect what we have. We have to do more to respect nature, and remember our place in it. Otherwise mother nature will remind us, and in ways we might not like," sums up van Lierop.

I doubt that any big developer will be inspired either by Frostpunk or The Long Dark and make frost an important element of any high-budget hit. I do not even know if I would like it, as it would probably mean shallowing the extremely intense, immersive experience. For another summer, these two games were enough for me. But their impact goes far beyond just the months when the sun glares at my monitor for hours, and leaving the apartment is like sticking your head inside an oven.

Frostpunk, its sense of hopelessness and the oppressive climate – all this inspired me to start writing my own stories. The work of the Hinterland studio inspired me to try winter hiking in the mountains, and in recent years, camping in the woods in December. So far, there have been no lethal situations, but, if necessary, I know not to worry – after all, The Long Dark taught me that each frostbitten limb takes away ten percent of maximum health points at most.

- winter

- survival

- Find Your Next Game

4

Author: Jakub Mirowski

Associated with Gamepressure.com since 2012: he worked in news, editorials, columns, technology, and tvgry departments. Currently specializes in ambitious topics. Wrote both reviews of three installments of the FIFA series, and an article about a low-tech African refrigerator. Apart from GRYOnline.pl, his articles on refugees, migration, and climate change were published in, among others, Krytyka Polityczna, OKO.press, and Nowa Europa Wschodnia. When it comes to games, his scope of interest is a bit more narrow and is limited to whatever FromSoftware throws out, the more intriguing indie games and party-type titles.

Latest News

- End of remote work and 60 hours a week. Demo of Naughty Dog's new game was born amid a crunch atmosphere

- She's the new Lara Croft, but she still lives in fear. Trauma after Perfect Dark changed the actress' approach to the industry

- „A lot has become lost in translation.” Swen Vincke suggests that the scandal surrounding Divinity is a big misunderstanding

- Stuck in development limbo for years, ARK 2 is now planned for 2028

- Few people know about it, but it's an RPG mixing Dark Souls and NieR that has received excellent reviews on Steam, and its first DLC will be released soon