Why We Hate – A Study of Online Anti-social Behavior

How is it possible that regular, nice people can become an aggressive horde of trolls once they launch League of Legends? Does the actual reason lie in… lack of eye contact? Our expert – a professional psychiatrist and an avid gamer – has all the answers.

“Let the hate flow through you” – said emperor Palpatine to Luke Skywalker aboard the Deathstar. The young Jedi, unlike his father, did not succumb to hate, but it was still nested deep inside his soul, just like other negative feelings, compulsively forsworn by the masters of the Light Side. Obscured somewhere between the mitochondria, it ultimately turned him into a grumpy hermit, a would-be murderer of his best apprentice.

FROM THIS ARTICLE YOU WILL LEARN:

- Why you should respect your dad;

- How many players regularly and intentionally try to spoil your fun;

- Is removing "toxic" players from the servers enough to get rid of the problem;

- What is the halo effect;

- What triggers the aggression of players – rivalry or brutality on the screen;

- What’s the online disinhibition effect;

- How the mirror neurons work.

We’re all haters

And although Star Wars was mere fiction, the series can teach us two important things: firstly, respect your dad, because there may come a day, when he saves you from the pale doppelganger of Pope Benedict XVI casting lightning bolts from his hands. Secondly – everyone has their own dark side.

This bitter morale casts a long and rather obvious shadow on the realm of computer games. Take, for example, Wonziu, my former editorial colleague, an honorary citizen of the city of Krakow, a member of the League of Handicapped Gentlemen, the custodian of the House of Doom – in short, a man, who can easily be described as the arbitrator of elegance of Polish YouTube. Unless, of course, you stumble upon a clip, in which this noble commentator of electronic entertainment sums up his opponents in a game of StarCraft in a language that’s as expressive and colorful as it is unfit for an elegant editorial such as this one, simultaneously pounding out some primal rhythm on the table with his fist (the glassware clinking in the background adds some subtle elegance to the whole scene), and then dismissing the whole incident with a nonchalant remark: "I’ll tell the neighbors I had a kitchen renovation."

He (or she) that has never sworn at the computer, let him (or her) first cast the stone, though. We all tend to discharge our emotions in a more or less expressive or vulgar way. However, the real issue arises not when the multitude of profanities (worthy of the mouth a drunken sailor) isn’t addressed to your computer or console, but rather to another person.

What’s antisocial behavior?

Such a situation is often referred to as toxic behavior, but I will be a little more precise and use the term “antisocial behavior,” defined as the active and intentional violation of social norms, often in the form of more or less direct aggression. In the field of computer games, we can include the already mentioned insulting of opponents or team members in a chat, but also any other behavior intended to spoil the fun of other people.

Teemu Saarinen's Oulu University publication [1] categorizes antisocial behavior in games within four groups: Flaming, i.e. insulting, whether in text or voice; griefing, i.e. abusing the knowledge of the mechanics of the game in order to interfere with other players (whether using exploits and obscure mechanics, blocking someone with your character if the game detects collisions, or lagging Minecraft servers by spamming bricks); cheating, most often using external software such as wallhacks or autoaims; and finally scamming, or robbing players of their virtual goods, for example by pretending to sell high-level equipment.

The extent and evaluation of individual occurrences depends on the genre of the game and the type of community around it, although in general, it can be said that cheating is possibly the most negative form of antisocial behavior, as it most often tends to ruin the whole pleasure derived from the competition. For the same reason, it’s most widely tackled by the creators. The others occur in different proportions in different games, and if only the mechanics of a given production permit exploits, one should expect them to take place at some point.

One of the possible ways of limiting antisocial behavior in games is simply rendering it impossible by removing certain mechanics. Flaming, for example, requires some form of text or verbal communication, so, for instance, Hearthstone features no chat. Of course, this doesn't mean that the players there are always civil on every level; everyone who has played Blizzard's card game for a long time has probably encountered a situation, where someone adds them to the friend list on Battle.net just to call them names.

In addition, even in a game limiting interactions between opponents so severely, there are other ways of making life unpleasant for the adversary, such as deliberately holding turns until the very end of the time limit. Removing certain mechanics in order to harness toxic behavior is, therefore, controversial and – although sometimes ineffective – quite simple, and thus a popular solution.

Anyone having enough experience with online games (two hours seems about enough) is likely to have encountered some kind of such behavior, so it seems that the extent of the phenomenon indicates that players are a gang of psychopaths logging in just to spoil someone's day. But there’s more to it, of course.

4%

According to a study from 2003 [2], players who intentionally and regularly behave in a toxic manner consist about 4% of the gross total of players. This is enough for everyone to encounter a cheater sooner or later, but also far less than the prevalence of antisocial behavior seems to suggest. At this point, it is worth recalling Luke's casus or the part about the youtuber at the beginning – although repeated inclinations to aggression in games are exhibited by a minority, everyone has their own dark side.

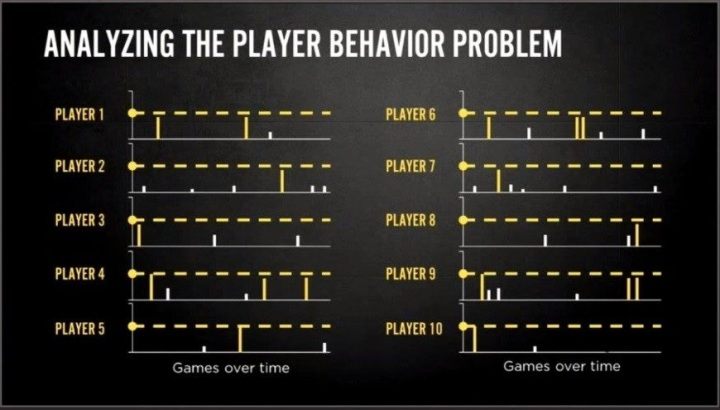

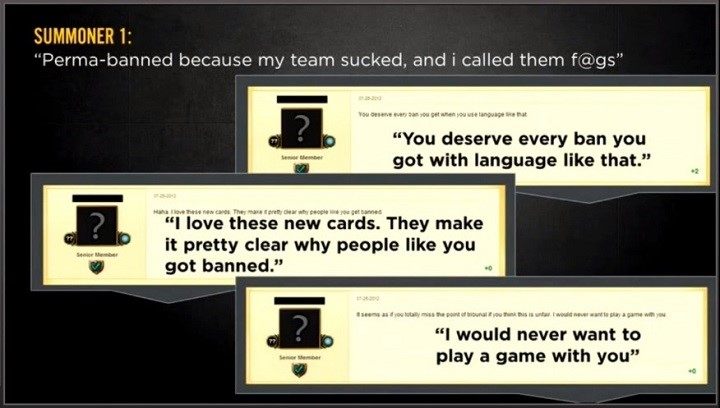

This has been proven by experiments conducted by Riot Games [3] with the aim of tempering the rather, well.... antisocial community of the League of Legends. A detailed review of the reports of unacceptable behavior was carried out, highlighting the particularly toxic players.

A HORDE OF TROLLS

How much is 4%? Let's take as an example the biggest and loudest game at the moment – Fortnite. In August last year, this title boasted a record 78.3 million active players. 4% of this number is 3,132,000. Let's write it again: three million one hundred and thirty-two thousand trolls. That's about as much as the population of Buenos Aires, and we're only talking about Fortnite and only about August last year.

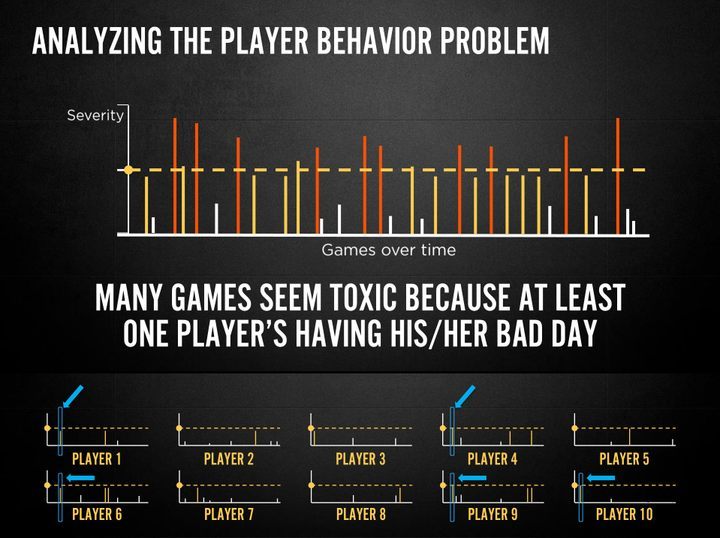

It is striking that antisocial behavior exceeding the limit set by the creators occurred not only in the case of particularly conflicting people but also in case of those from the "normal" group. This observation is particularly important because the League of Legends is a team game. Removing "toxic" players is not enough to get rid of the problem, or to even minimize it. If 10 people take part in a session, each of them behaving inappropriately in only 10% of the matches, a simple calculation of probability allows us to estimate that we have as much as 65% chances of experiencing antisocial behavior during every single match!

As if that wasn't enough, toxicity often triggers a symmetric response from other players. Research from 2015 shows that half of griefing players experienced griefing and behaved unacceptably in retaliation. This leads to a dangerous snowball effect – a single antisocial player can escalate the problem and spoil the fun of everyone on the server.

In the same way, it makes justifying oneself a lot easier, because if everyone is rude, why should I be the last righteous one? Equally, since others use cheats, I, too, have the right to do it to even the odds. If someone’s calling me names, why should I remain silent?

It is also worth remembering that players do not have access to the stats used by Riot Games when conducting the research. If a person defames someone in a chat once a year, they will be automatically recognized as a hater by others, who have no reason to think that the given player is just having a bad day and that they usually don’t behave like this. This creates the illusion that most online gamers are antisocial.

The Heart of Darkness

There are not many players who notoriously violate social norms, but from time to time it happens to everyone. What is so tempting about it?

Above all, we do it because we can. Players, perhaps contrary to popular opinion, do quite well with distinguishing fiction from the real world and are well aware of the fact that games are just entertainment. In the game, a person can afford more – including more emotional behavior – and do things they wouldn't dare in real life. This is known all too well to every GTA fan (and therefore – a considerable portion of the planet's population), who terrorize the streets of Los Santos, despite having absolutely no intentions to do so in real life.

Antisocial instincts – and everyone has them, although few admit it – are simply extremely easy to discharge in a game. Laying phallic constructions from stones in your neighbor’s garden would, at best, meet with doubts about your mental stability, but if you do the same thing in Minecraft, nobody’s particularly concerned about it.

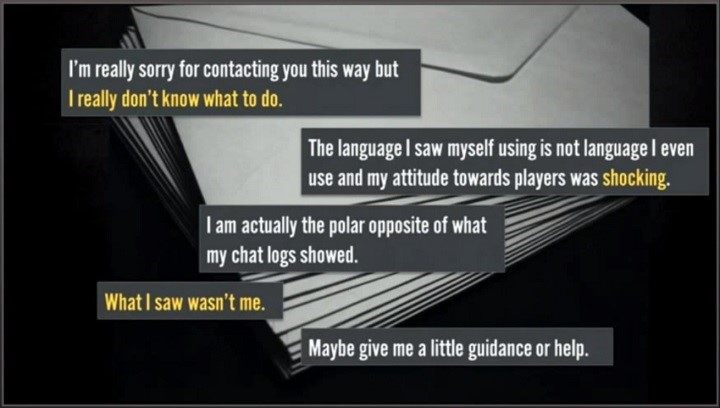

In this way, however, I am referring only to the simple need for a little bit of malice, silliness or conflict in life, and I’m thus simplifying the matter. After all, human behavior is not a product of a brain isolated from the environment, the only purpose of which is to fulfill its ill desires. Such a line of thinking is one of the most common cognitive biases, called the fundamental error of attribution [4]. It consists in the fact that when assessing someone's behavior, we usually do not take into account all the factors that may have influenced it – we believe that someone is behaving badly because that’s what they do. The fact that someone may have been fired from work on that day, or dumped by their girlfriend or boyfriend, and happened to get Fallout 76 for Christmas usually does not matter, or even occur, to the observer.

SOMETIMES PEOPLE JUST EXPLODE

In psychopathology, there exists the concept of acting-out [5], which means a violent discharge of emotions through behavior unrelated to the actual factor that triggered them. It can be realized by responding with pathological gambling or compulsive drug use, but also beating someone up for the deeds of another, or calling a random person in StarCraft “a moron.”

Acting-out itself is a notion used in describing mental disorders, related to the loss of self-control and being ignorant of the consequences. In the case of healthy people, however, it is often possible to observe similar ways of venting frustration, which, in principle, differ only in quantity. Screaming at the computer because someone is winning by pure luck, rather than skill, is neither rational, nor constructive, nor even tactful. But it feels good and it helps.

The fundamental attribution error makes it difficult to appreciate that, in most cases, antisocial behavior is caused by external factors. It is true that the discharge of emotions through aggression is an extremely immature defensive mechanism, but in some situations, it is completely sufficient. Without noticing this, it is easy to consider a critic to be a hater, or to patronizingly say that they were acting in order to improve their low self-esteem. And such simplified thinking basically brings us to the same level of antisociality once we verbalize our suspicions.

An example of similarly simplified thinking is the so-called halo effect [6], i.e. the unconscious attribution of personality traits to others on the basis of the first impression. These are strongly emotional attributes, often associated with some kind of a stereotype. Seeing an elderly, elegant man in a lecture hall, it is easy to assume that he’s a wise man of letters with extensive knowledge, even though he may just as well be a dilettante slipping through the net his whole life. On the other hand, when we see a homeless man, we assume that they’re an alcoholic not trying to improve his or her existence, without taking into account that for all we know, this man or woman may be a talented entrepreneur who lost everything a month ago due to a mistake made by the Tax Office, or was cheated out of business by an acquaintance.

It's just as easy to say that the brazen camper from the opposite team eats kittens for breakfast and is a mafia hitman, so maybe offending him won’t be such a terrible crime. I'm of course exaggerating – the effect is unconscious and although we probably don't consider our opponent a bad person at the level of logical reasoning, a negative emotional attitude often prevails.

Tribal instinct

Interestingly, game developers often deliberately reinforce the negative perception of the opposing team. Simply attributing the color red to them (in opposition to the blue or green icons of allies) makes us subconsciously associate them with a threat, to which you have to react immediately, usually in a rather aggressive way. Even when the distinction between the two teams is not so clear-cut, the fighting groups are often deliberately antagonized on the plane of lore or design. A person who identifies with the Alliance will feel contempt towards a wild and senselessly cruel Orc, while the badass from Horde will secretly despise the shiny, dandy member of the Alliance.

The very direct reference to tribal instincts is intended to boost emotional engagement and increase involvement, even at the cost of bypassing the rational part of the brain and generating excessive aggression. This is not bad per se (after all, bloody FPS games are all about alleviating aggression) – as long as emotions remain on the level of gameplay, and don’t define the relations between players.

Another cognitive bias stemming from the antagonization of competing factions and provoking antisocial behavior is the out-group homogeneity effect [7]. We tend to consider the opposing team more homogeneous than it is in reality. Because of this, noticing individual members sometimes requires effort; it is easier to treat opponents as an undifferentiated mass of cannon fodder, rather than as a group of real people. This, in turn, can lead to the depersonalization of opponents, which facilitates the discharge of negative emotions when they simply turn out to be better at the game.

The out-group homogeneity effect is a mechanism widely used in all kinds of propaganda texts designed to discredit certain social groups. It’s always “us” against “them”; simply being on the other side makes you as bad as the worst member of the group – you don’t usually go wondering what dreams and aspirations the stormtroopers had, or whether they joined the army willingly.

The mechanisms described above are strongly intertwined with the fabric of competition. It would seem that rivalry in itself is a factor increasing the chances of antisocial behavior among players, and games based on cooperation are less likely to be affected. Studies show that this indeed is the case. Moreover, a comparison of the impact that either rivalry or brutality have on the level of aggression of players makes it quite clear that the former significantly increases it, while the latter, in principle, has no measurable effect. You might want to bear this conclusion in mind next time you hear someone claim that violent computer games turn children into murderers, unlike the classic, one-hundred-percent competitive, sports.

For the unbelievers, I recommend logging in to a game devoid of a competitive aspect, preferably based on building, and then try some MOB and see in which of these you’ll be insulted sooner. This does not mean, of course, that antisocial behavior is impossible to encounter in construction-based games, but the indecent-looking creatures in Spore, or fecal-like street layout in SimCity, bothers me much less than verbal aggression.

The above examples roughly explain why toxic behavior is so prevalent in MOBA games. As highly-competitive and team-based productions, these games easily amplify aggression and are a natural environment for the out-group homogeneity, and halo effects.

On top of that, in games such as Counter-Strike, for example, one skilled player is able to win a match even if all members of his team suck. In most MOBA productions, on the other hand, the team is as strong as its weakest link, so anger can also be addressed to less-skilled players from your own team. Then, there’s the problem with time investment – if the result of a 30-mins game is determined from the onset due to the imbalance of forces, it can really rub you the wrong way, which is furthermore difficult to discharge with a typical ragequit, as these are punishable in most games of this type.

However, all that wouldn’t be so important if we maintained the same level of restraint as we do in real life. As we’ve already established, players more inclined to antisocial behavior are a minority – why, then, the shopkeeper from the store across the street, who’s never raised his voice on anyone, insults random people in League of Legends during after-hours?

What comes into play here, is the online disinhibition effect [8], mentioned in his research by John Suler in 2004. The simple conclusion was that people behave differently online than in real life – we breach certain social barriers, which we wouldn’t dare to in personal relations. This effect is bipolar – the disinhibition can either be positive, when, for example, your telling all about yourself to someone you’ve just met on the internet, or negative, when you’re using the blessing of high-bandwidth internet connection for discharging aggression without nearly the same level of control you exhibit in, say, your workplace. For Suler, there are numerous reasons for that, including anonymity, the disengagement of the online reality from the real one, and, consequently, of our real-life ego from its digital emanation, which, in turn, allows us to behave differently, to do more.

However, I find the explanation formulated in 2012 much more plausible. It turns out that the factor most strongly amplifying the effect of online disinhibition, especially the negative one, is the lack of visual contact. Why is eye contact so important? In a natural environment, our antisocial instincts are effectively suppressed by empathy. We do not want to hurt someone, because it will cause a negative emotional response also within ourselves. In most cases, harming people is simply unpleasant, which is a natural evolutionary mechanism necessary to maintain social cohesion. Thanks to the fact that we feel bad when others suffer, we help each other, we work together, and open conflict is really more difficult than it seems.

Of course, there are lots of simple ways to drown out the empathy – after all, crime, war, and abuse do not come from nowhere. In general, however, people feel uncomfortable when suffering surrounds them, and this effect often occurs even in extreme conditions – especially when visual contact with the victim is maintained. A trained soldier will probably be able to kill someone even when looking in their eyes, but shooting somebody in the back is still going to be much easier. The face is the main medium of emotions, so without seeing it, it is easier for us to ignore them, and thus inflict harm upon the other person. The face is also the most important visual component of identity, so it’s not easy to objectify the victim and deny his or her humanity having their face in front of our eyes.

From the neurobiological perspective, the so-called mirror neurons play a key role here. Mirror neurons are activated when an activity or emotional reaction is observed in another person. They are also activated when we ourselves experience these feelings or make these gestures. It follows that, in principle, the state of the brain is nearly identical no matter if you’re watching, or experiencing. We have no problem repeating what someone shows, or decrypting his or her emotions – to some extent, it makes no difference for the brain whether we see sadness in another person, or feel it ourselves. That's why it's easier to discuss difficult matters over the phone – if you don't see the other person, the mirror neurons are silent, and you’re “safe.”

The same applies to games – without seeing other players, we are still exposed to cognitive errors, which mainly result from a simplified way of thinking and don’t require visual stimuli, while the otherwise very effective evolutionary protection against harming others is significantly impaired.

Those were the days; those will be the days

There also are people who claim that the antisocial behavior we’re discussing here is not antisocial in the least. After all, the rules on the web are different and there is no point comparing them with those that govern real life; if the game allows you to do something, why should anyone punish doing it. As an argument, they refer to the beginnings of computer entertainment, when scamming, for example, was the order of the day and nobody thought of it as something negative.

Possibly every Tibia veteran was at least once deceived by another, who sold them some useless piece of rubbish for an exorbitant sum, changing an item in the transaction window in the last second. The natural reaction was not to report this problem to administration – although it is worth remembering that such a possibility also existed – but to grab your axe (if you were playing a knight) and bash the living soul out of the thief, to the delight of the surrounding mob. Not to mention the "fast hands" minigame, rather popular in the Tibial world, which was basically scamming with rules (which nobody followed anyway).

You should also remember about player killers. Annihilating other players was sanctioned in Tibia to some degree, but a balanced fight with an opponent with similar stats was more unfavorable for the aggressor than oppressing and maliciously killing characters several dozen levels below you. That's why the worlds with PvP enabled were full of powerful knights or mages that would kill newcomers just for kicks. Sounds like hell on digital Earth? Nope! For many players, escaping PKs was one of the funniest experiences, especially when you could face them with a group of friends. The satisfaction from escaping and suddenly turning from prey to predator was incomparably more fun than completing even the most difficult dungeons.

Chat moderation was also rudimentary – if it was there at all. If you were insulted with a bunch of words you didn’t even understand, you just shrugged your shoulders and played on. There were even some positive aspects of that – death threats, nowadays very common, were not even there – because why threat someone in real life, if you can treat him with a ball of fire without a warning in the game? And then possibly utter the legendary "hunter" as well, so that the victim knows they’re dead; that there’s no force in the entire Universe that will save their wives, sisters, children, and mother. As long as, of course, they were playing Tibia, too.

However, times have changed, and games, to the despair of the old guard, are no longer niche entertainment for maturing men thirsting for bread and games. With a growing number of players, followed by bigger money and bigger expectations, games had to become a bit more civilized over time, to create a more formal and observed etiquette, moderated chat, eliminate aggressive or damaging behavior.

This is a natural part of the evolution of the medium, and it seems that most players think this is the right direction. After all, no one would like their younger sibling or, even more so, child to experience some kind of unpleasant behavior from antisocial individuals in any game.

And only sometimes, when everyone’s asleep, when the light is dim and noises hushed outside the window; when all the stress and setbacks accumulated over the week ring in your head; only then, and sometimes, you wish you could go back to the times when everything was simpler. To the lawless Wild West of video games. That's when the Dark Side starts to become itchy. When the mind falls asleep and the monsters wake up.