The Right to Chip In? Or Why We Need Neuro-regulations

Some scientific advances require regulation more than others. In the case of neuro-laws, which provide the framework for access and limitations of neurotechnology, failure to prepare legal provisions in time can have dire consequences.

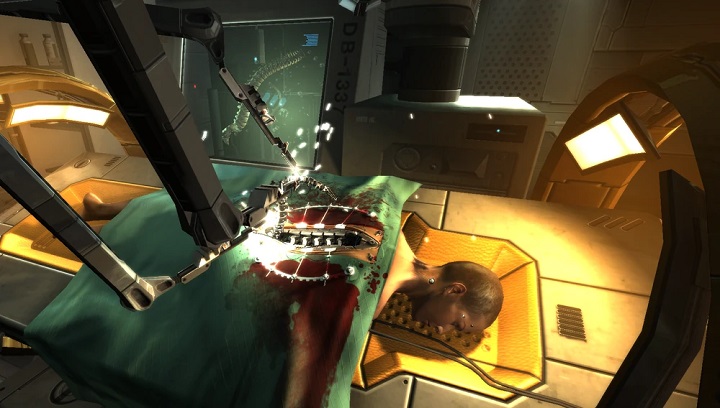

In Deus Ex: Mankind Divided, a game whose story begins just four years from now, augmentations of body and mind are a daily occurrence. Groups opposing transhumanism rebel, and the main character, Adam Jensen, transformed by experimental implants into half-human, half-machine, is treated like a pariah – however, the world is slowly getting used to the vision of cybernetic enhancements. We still have a long way to go with this scenario, but don't kid yourself: just because we're not passing people on the sidewalk looking like Robocop, doesn't mean implants aren't changing people's lives already. Sometimes to such an extent that their removal is equivalent to destroying someone's identity.

Five rules of the neurotechnology era

The issue of neuro-rights may seem out of sci-fi book, but in the face of rapid technological advances, it must be taken very seriously. Last March, Smithsonian Magazine reported on a completely paralyzed man who, using a brain-computer interface (BCI), was able to connect with researchers and his family. Four years ago, The Guardian reported on six blind patients who regained partial sight through the use of an implant that transmitted images directly to their visual cortex. Technology enters our brains and regains senses for us, and while it may not be quite as spectacular as in Deus Ex, its rapid development raises concerns about whether our existing laws can handle this issue, which they probably can't right now.

Organizations such as Neurorights Foundation are calling for the expansion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to include neurorights: regulations guaranteeing people's protection from the misuse or abuse of neurotechnological devices. Their advocates focus on five issues:

- Mental privacy – all data obtained by examining brain activity should be kept confidential. If stored, there should be an option to delete them at the request of the player. The sale, transfer, and use of this type of data should be "strictly regulated."

- Free will – individuals should have ultimate control over the decisions they make, without unknown influence from external neurotechnology.

- Equal access to cognitive augmentation – guidelines should be established at both international and national levels, regulating the use of neurotechnologies that enhance the mind. These guidelines should be based on the principle of justice and ensure equal access.

- Protection against bias – anti-discrimination measures should be the standard for algorithms used in neurotechnology. The algorithm design should include information from user groups to prevent bias.

- Identity – boundaries must be established that would prohibit technology from interfering with the sense of identity. When neurotechnology connects individuals to a virtual network, it can blur the line between human consciousness and external, technological stimuli.

One of the main goals of The Neurorights Foundation mentioned earlier is to create a new Hippocratic Oath. One that would be specifically designed for entrepreneurs, companies, scientists, and anyone working on advances in neurotechnology. The Technocratic Oath is based on seven pillars: benevolence, harmlessness, autonomy, justice, dignity, privacy, and transparency. Her supporters hope that even though committing to follow it wouldn't be legally binding, widespread acceptance of these rules would reduce harmful practices for users of new technologies.

The story of a woman, described in a paper published in May 2023, "How I became myself after merging with a computer: Does human-machine symbiosis raise human rights issues?" by Frederic Gilbert, Marcello Ienca and Mark Cook, discusses how neurotechnology can impact a person's identity and mental state, as well as the need to regulate not only access, but also the revocation of this access.

Rita. Symbiosis

Until 2010, Rita Leggett's life was far from "normal." She barely left her house, couldn't go to the store alone, and lived in a state of constant tension.

At the age of 3, she was diagnosed with severe epilepsy; the attacks, occurring on average about 3 times a month, were described as "brutal." She tried all sorts of therapies for decades, but none of them worked. Just before turning 50, she decided to participate in clinical trials of Neurovista's brain-computer interface, designed to help people struggling with epilepsy. Rita had four electrodes implanted, which monitored brain activity and looked for patterns signaling an impending epileptic seizure. When it detected him, information was sent to an external device, which warned her about the probability of an attack.

The Neurovista implant did not help all of the volunteers, its effectiveness varied greatly depending on the individual. However, it worked miracles for Rita. The number of seizures has practically fallen to zero. Since Rita had to take her anti-epileptic drugs herself, she had a sense of decision-making instead of being left at the mercy of a computer in her head. In fact, she stated that she had become one with the implant:

[The BCI] was like an alien at first, you grow gradually into it and get used to it, so it then becomes a part of everyday, [...] it becomes part of you. Because that's what it did, it was me, it became me, [...] with this device I found myself [...] It changed who that person was then and I found myself changing... growing I suppose.[*]

In no time, Leggett realized that with the Neurovista implant, she could do things she couldn't do before: socialize, stay home alone, drive a car. Scientists who studied her case defined the relationship between the patient and the device as "symbiotic": readings from her brain helped to improve the algorithm, she experienced a fully ordinary existence for the first time in her entire, fifty-year life.

Who owns the rights to dreams of electric sheep?

In Rita's case, the implant allowed her to recreate her own self. But foundations dealing with neuro-rights don't just focus on the potential positive effects of developing neurotechnology capabilities. For example, Rafael Yuste, a neurobiologist from Columbia University, conducted an experiment in 2019 in which he made rats see things that didn't actually exist, using electrodes implanted in their brains. The prospect of doing something similar with the human mind was so terrifying that Yuste began to strongly lobby for curbing neurotechnology development until legal frameworks for it were established.

But the move towards neuro-rights is not just about manipulating augmentations. There are also much less spectacular, though not less important issues. Once we are able to read memories using implants, where will we draw the line in interfering with them, for example in trauma treatment? Who will own the content of our dreams once they're read by a computer? To what extent should doctors be allowed to interfere with human thoughts in order to stop self-destructive or dangerous behaviors? Where should we draw the line in matters of improving our mental abilities?

It may seem that such considerations still smack more of Philip K. Dick's novels than of everyday useful legislation, but such regulations will allow, in the future, in which we will be able to record our thoughts on computer disks, to meet the challenges of neurotechnology unleashed. If you feel this is excessively vigilant, Rita's story specifically demonstrates how the lack of defined neuro-rights a decade ago could have severe consequences.

Rita. Removal

Rita's normal life didn't last. Just over two years after they put the implant in her brain, Neurovista was on the brink of bankruptcy. The BCI clinical trials have been interrupted, and the participants have been advised to remove the device. Ultimately, the company's bankruptcy meant there was no way to fix things if they stopped functioning properly. But by that time, Rita was already fully attached to her implant and the sense of security it gave her.

My device became as dependable as time itself. Your alarm clock that wakes you up in the morning to get you to work on time! Your appointments for that day! Checking the weather forecast. To decide what to wear! If you can go for a walk, to the beach or a picnic etc. We use mobile phones every day, we rely on them all the time. People are attached to these things more than they realise and think nothing of it! Why then would it be so strange for me, myself to become so attached to [the] device and feel that we became one and I felt safe and secure?

The woman did not want to reconcile with the prospect of losing the implant. Rita's implant was removed as the last one from the group of Neurovista test volunteers. Earlier, she and her husband tried to negotiate with the company, fighting at all costs to keep the device. There even arose the prospect of mortgaging the house. All in vain: in 2013, after over two years of normal life, she returned to the starting point. She kept telling the scientists:

I wish I could've kept it. I would've done anything to keep it. [...] I wanted to stay with it [...] I would've done anything, I would've paid money, I would've done anything if I could've.

Who killed Rita Leggett?

Scientists studying Rita's case talk about a "symbiotic organism" just as much as they talk about her. The woman changed so profoundly under the influence of the implant – experiencing a new sense of agency, not living in constant fear of epileptic seizures, opening up to activities she previously had to avoid – that she almost became a different person. Meanwhile, removing the brain-computer interface meant nearly the end of that person's existence. Rita Leggett lost part of her new personality along with the implant. And if a private company had the ability to force her to get rid of the device – even if for noble reasons, such as concern for repair and serviceability – it would render the "new" Rita a property of Neurovista company.

Rather, the company was responsible for the creation of a new person. The device was the property of the company, not of the patient, despite the fact she appropriated the de novo agential capacities – resulting in an existential dependency with the BCI. In a way, the company owned the new person; as soon as the device was explanted, that person was terminated.

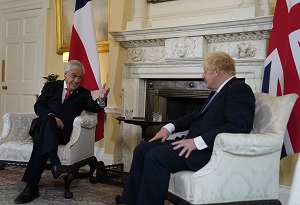

In 2021, Chile became the first country in the world to include provisions for the protection of neuro-rights in its constitution. The amendment introduced less than two years ago was written with the participation of The Neurorights Foundation and the Chilean Kamanau Foundation and was unanimously adopted by members of both houses of parliament. Its content reads:

Scientific and technological development will be at the service of people and will be carried out with respect for life and physical and mental integrity. The law will regulate the requirements, conditions and restrictions for its use by people, and must especially protect brain activity, as well as the information from it.

In the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, one of the first articles speaks of the universal "right to respect for individual's physical and mental integrity." The right – inalienable and applicable to everyone – should, according to one researcher, not cease even when loss of mental integrity is linked to the removal of an implant installed with user's full consent. Rita is Australian, so EU regulations do not apply to her, but even if they did – can existing regulations even settle this type of dispute? Could it be that, since we live in times of problems taken straight out of Blade Runner, should we pause for a moment from the pursuit of progress and spend a few jolly moments taking advantage of humans' unique ability to think ahead to avoid side effects?

Rita. Loss

Rita remembers her implant like a lost friend:

We had been surgically introduced and bonded instantly. With the help of science and technicians we became one. We did together what was expected of us! We performed beautifully? To this date, I have never again felt as safe and secure. Nor am I the happy, out-going, confident woman I was. I still get emotional thinking and talking about my device, and I miss terribly having the security of it.

The scientists investigating Rita's case mention feelings of interrupted symbiotic relationship with the device; lost agency, emotional pain, cognitive and psychological uncertainty. Loss and mourning.

Stolen identity.

Living without my device was very hard at first. I always felt like there was something missing, I'd forgotten or left behind... a part of me! [...] My confidence in myself was shattered. Doubting every feeling. Asking or questioning myself all the time. [...] Am I safe? [...] How will [I] cope and live without my trustworthy dependable part of myself... [...] Staying home alone is scary. [...] I do not go out much unless I'm with my husband. My social life is not existent now.

They took away that part of me that I could rely on.

To finally switch off my device was the beginning of a mourning period for me. A loss, a feeling like I'd lost something precious and dear to me, that could never be replaced: It was a part of me.

*All quotes are from Frederik Gilbert, Marcello Ienca, and Mark Cook's work "How I became myself after merging with a computer: Does human-machine symbiosis raise human rights issues?"

Sources:

- Frederic Gilbert, Marcello Ienca, Mark Cook, How I became myself after merging with a computer: Does human-machine symbiosis raise human rights issues?, Brain Stimulation Journal

- Jessica Hamzelou, A brain implant changed her life. Then it was removed against her will, MIT Technology Review

- What are neurorights and why are they vital in the face of advances in neuroscience, Iberdrola

- Nora Hertz, Neurorights – Do we Need New Human Rights? A Reconsideration of the Right to Freedom of Thought, Springer Link

- The Neurorights Foundation