Total War Against Pirates – The History Of DRM Protection

DRM sometimes serves as an extremely effective form of protecting games against pirating. However, since the industry is waging a total war against this phenomenon, honest users are also affected. Let's take a closer look at the evolution of DRM.

The image of a pirate as we know it best from history includes a ship, a cutlass, a peg leg and a parrot seated on his shoulder, as well as a particular partiality to gold. For several decades, however, this image has gone through a complete makeover. Modern pirates come in different shapes and sizes. Some are skinny, and some are fat; some wear glasses while others are dog owners, but all of them have a computer with an Internet connection, and the thing they value most is not the shiny metal but bytes that make up everything that can be saved to a disk. How to fight them? Developers, especially those who create games, have their secret weapon. It's DRM – Digital Rights Management.

Of course, DRM does not exhaust the topic of anti-piracy protection, but recently it has become synonymous with actions designed to hinder software pirating, and is going to be the focus of this article. The very phenomenon of copying games and programs is basically as old as the industry itself, and the first methods introduced to prevent the creation of illegal copies of various works were at the same time strange, creative, funny, and annoying (the latter characteristic is still valid today).

Initially, people copied everything there was to copy – paper tape for Altair computers or cassette tapes with software – or didn’t copy at all, because the cost of equipment designed for this purpose as well as that of the media was too high. With the rising popularity of the floppy disk, first measures were introduced to protect the content they contained. E.g. the first PC game in history, Microsoft Adventure from 1981 (previously existing as Colossal Cave for PDP-10 computers), had the so-called bad sectors, whose presence on the floppy disk allowed the machine to check whether the medium was original. Of course, this type of protection instantly prompted the creation of a tool designed to neutralize it, which appeared in the form of Locksmith copier. The process of introducing copy protection only to see a counter-tool appear instantly began as early as three and a half decades ago and continues to this day. You can read about the various more or less interesting ways to make the life of a pirate more difficult in the boxes. The article itself will focus on the tools that appeared in the 21st century.

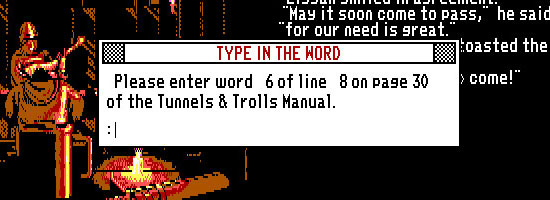

Prior to DRM #1 – instructions

Once upon a time, when the Internet was not yet a thing, the creators protected their games by making the players search for a specific word or character in the instruction attached to the product. One of the first games to benefit from this solution was Elite from 1984. Of course, we could always make a hard copy of the instruction, so soon inventions started to appear such as the teeny tiny booklet with a multitude of pages attached to Alone in the Dark, which quite effectively deterred gamers from the arduous task of making paper copies.

SafeDisc, SecoROM, and StarForce

I’m sure that everyone who’s reading this article has heard of at least one of these systems, which operate on the basis of a unique digital signature attached to the original game medium that is very difficult to copy (SafeDisc), the verification of the physical location of data on the disc (SecuROM), or counting the number of sectors on the disc (StarForce).This is just the tip of the iceberg, because the reality was far more complicated for the pirates and honest players alike.

SafeDisc was relatively little annoying, but its effectiveness was limited too – confirming the presence of a digital signature on the CD was quick, and the program launched smoothly (this, of course, required the original disc in the drive), and upon its removal everything was in order. An idea to fight with this system came in the form of drive emulators such as Daemon Tools or Alcohol 120%, which were later detected by subsequent versions of SafeDisk, which in turn forced the installation of a program "hiding" the emulator. That's a lot of effort to make, but SafeDisc never posed too much of a problem to the displeasure of software developers.

SecuROM, in turn, is a completely different league. The program verifies the location of data on a disc, but it used to do something much worse – it limited the number of installations of a given game. From the perspective of a typical player it was terrible: he or she would buy the game, install it, have fun with it, but for various reasons (change of computer, disk formatting, etc.) was forced to reinstall it – after several times it was necessary to call the developers and prove that what we had was in fact an original version to have the limit increased. That's not all: more often than not SecuROM couldn't detect an original disc placed in the computer and wasn't compatible with some models of optical drives, and the presence of virtual drives (and sometimes even anti-virus programs) caused conflicts, whereas the tool itself remained on the hard drive upon removal of the protected title. Of course, pirates installed and uninstalled the games without much effort.

Perhaps the most well-known examples of causing inconvenience for honest players are BioShock, Spore and the PC version of Mass Effect. The first game allowed for only two default activations – later we had to politely tell someone on the other side of the telephone line that we needed to reinstall the title once more. This limit was quickly raised to five installations, because the non-US players couldn’t call anyone locally, and what’s even worse the first batch of games had the wrong hotline number printed. In 2008, this restriction was removed, leaving only the necessity of online key activation. Seems cumbersome? Well, the implementation of this measure meant that there was no pirated copy of BioShock for 13 days after release.

The two games published by Electronic Arts, Mass Effect and Spore, were to be equipped with both SecuROM and a system requiring regular authentication of the game every 10 days, which of course called for an Internet connection. The pressure of the public forced the company to abandon this idea, although the activation limit remained in place and, what's even worse, it was not subject to resetting (EA initially failed to release a tool to "recover" activations during the installation of the game).The answer of the community? Spore became the most "pirated" title of 2008 (1.7 million downloads via torrents), and Electronic Arts also had to deal with several lawsuits related to the presence of SecuROM on the CD-ROM containing the game.

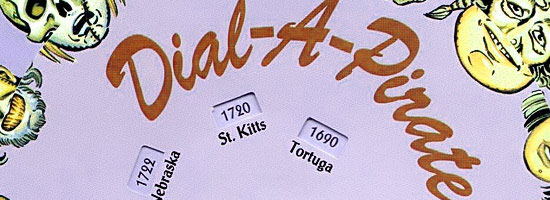

Prior to DRM#2 – code wheel

Another measure consisting in having the player search for characters in the instruction was the code wheel. Such a tool usually included two superimposed, rotating circles with separately printed, e.g. faces of pirates (The Secret of Monkey Island).The game asked the user to match the elements on the carton so as to enter the correct answer (character, word, name). Losing the wheel made it impossible to play. The last production to use this type of protection came as late as four years ago – it was an adventure game entitled Edna & Harvey: Harvey's New Eyes.

The most powerful player in this category was StarForce. The product of the Russian programmers was designed for two of the most "piracy prone" markets in the world: Russia and China, so there was only one guideline – to create something that couldn’t be broken. On the one hand, the measure implemented proved to be very effective, because the StarForce-protected Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory wasn't followed by a pirate copy for 422 days and to this day remains one of the record holders when it comes to challenging the crackers. On the other hand, StarForce remained on the computer even upon removal of the game and was accused of physically destroying the optical drives and basically being malware. There was even a lawsuit filed against Ubisoft because of the use of invasive protection that was StarForce. After 2 years, the lawsuit was dismissed for lack of evidence. The distaste, however, lingers to this day, which is one of the reasons behind StarForce being virtually absent in the western markets.

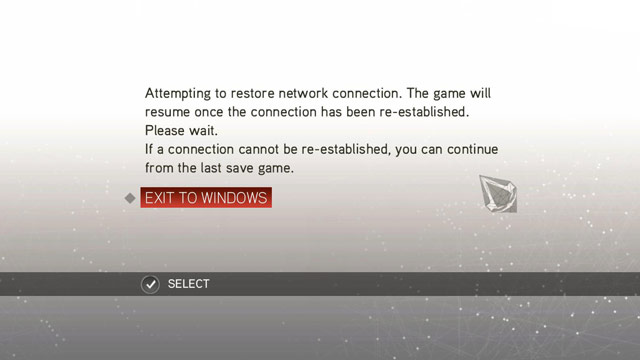

Online key activation is one thing; after all you can connect to the Internet to launch a newly acquired game even when you're deep in the wilderness. But when a developer demands a constant online connection from those of us who only want to play a story campaign that has nothing to do with multiplayer mode, we just might get angry. This was the case of Assassin's Creed II, Diablo III or the new SimCity.

The premise is simple: the game must be in constant contact with the server of the company so as to ensure the creators that the user has an original copy of their work. This practice is usually hidden under the guise of supposedly easier provision of updates, improving social functions, or quicker switching between the single and the multiplayer modes. In reality, however, for those who want to enjoy the story in the comfort of their own room, "sharing" and "achievements" are the last priority, and this whole situation is one great inconvenience. After all, every network infrastructure, even the best in the world, will never be one hundred percent reliable, and breaking the connection with the server during the game means being unable to continue playing and losing the progress since the last saved game.

After a few blunders (e.g. Rainbow Six: Vegas 2 asked the players who had a digital copy of the title to place a disc in the drive, which was of course impossible – the remedy came in the form of borrowing a crack from the Reloaded warez group) Ubisoft launched the game Prince of Persia in 2008 without any protection measures to verify how truthful were the players who claimed that DRM is evil and compels honest people to "pirate" thus protected titles. The result? More than 20,000 illegal downloads within a day since the launch of the game. Therefore, the DRM-based approach returned. Silent Hunter 5 was based on a continuous connection with the servers – a problem that the crackers tackled on release, whereas Assassin's Creed II made the pirates work for a month.

In 2012, the management of Ubisoft officially abandoned this type of protection. Interestingly enough, it's the same year that the long-awaited Diablo III launched, putting millions of players on edge with the same type of DRM. This protection prevented many people from playing for several weeks after the May release. The infamous Error 37 meant problems connecting to Blizzard's servers, which was an obvious mistake on the part of the developer. There was a good intention behind this decision but the result was far from perfect. Diablo III went through serious problems soon after its release, but with time everything went back to normal, servers ceased to act awry, and the gamers got accustomed to the implemented solutions, playing for several years now without any major obstacles. The title was a huge success, and one of the reasons behind it is probably the fact that until today there has been no functioning pirate version. Apparently, a constant online presence (even if you play by yourself) can be achieved, although in the case of Diablo we are dealing with a production that's basically multiplayer and is constantly optimized by the creators.

Prior to DRM #3 – a book with instructions

In the case of King's Quest VI the medium containing the game was accompanied not only by an instruction, but also a special book derived from the universe of KQ. The volume entitled Guidebook to the Land of the Green Isles included a printed alphabet of the ancient people, the knowledge of which turned out to be necessary to solve one of the puzzles in the game. Without the book you got stuck.

At times, fighting against piracy can be amusing. Actions taken by some developers were a nuisance only for the holders of illegal copies, and we could see a substantial dose of creativity and humor in their solutions.

Instead of using sophisticated activation systems, the creators of titles such as Alan Wake, Serious Sam III or the third installment of Settlers modified the content of the game so as to spoil the fun for the illegal users. The production of Remedy is a lightweight representative in this category, because illegal copies of their game worked just fine except for one seemingly inoffensive item. The character of Alan was wearing an eye patch throughout the game – you can imagine the impact of such a joke on the somber atmosphere of the production...

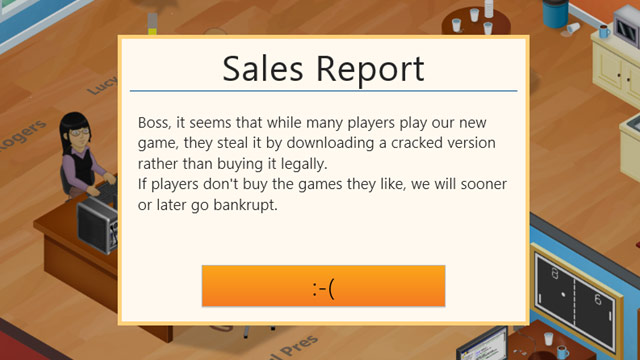

A similar, strictly "pirate-y" treatment was also implemented by the authors of DIRT Showdown. Illegal copies "communicated" with the players through humorous lines delivered in a way characteristic of Talk Like A Pirate Day. In turn, a game about making games, namely Game Dev Tycoon, made the pirates walk in the shoes of an author who was stolen from. If the production was gained from dubious sources, after some time it announced to the player that the sales of their new virtual work looked poor because too many people download it illegally. Nice one!

Other developers outdid themselves in their wickedness. The fourth installment of Sims in its "warez" version gradually censored the entire game screen. Standard pixels covering a sim in the bath magically spread to everything that was in sight. In Crysis: Warhead after a few minutes all types of weapons began to shoot with chickens instead of bullets. And since we're on the topic of animals, let's not forget Settlers III, where pigs were forged instead of iron, which subsequently made ??it impossible to create an army, and translated into prompt defeat.

There’s a couple of other examples that should be mentioned in this category. Serious Sam III is a game that requires a connection with Steam (you can read about this topic further in the article), but Croteam decided to equip the game with an extra protection. Pirates who wanted to dispose of an army of space invaders without paying stumbled upon a superserious, superfast scorpion that would attack our brave Sam without mercy. Another example features CD Projekt Red, a developer known for repeatedly voicing its opinions on DRM and siding with the opponents of this solution. But this doesn't mean that the creators of The Witcher are not fighting against piracy. Assassins of Kings was equipped with several types of malicious bugs. For instance, Geralt was killed during cutscenes or had crowds of kids following him, or every love scene showed our protagonist getting busy with the rather unappealing Marietta Loredo.

In addition to thwarting the fun, the main objective of such tinkering with the game code is to stigmatize the pirates. A countless number of players with illegal copies wrote on forums (including those official) about the errors in the game and asked the developers for help in removing them, or downright accused the authors of releasing useless conversions or spending too little time testing the game.

Valve and the venerable keeper of PC gaming, Gabe Newell, are well respected in the gamers community. Of course, nobody is perfect (as evidenced by the angry growl on the news about paid mods on Steam), but the creators of the Half-Life series are among the leading teams that are both liked and appreciated. But let's go 12 years back and look at the intentions of the creators accompanying the release of Half-Life 2, which from the very beginning were to be linked to a certain new service of the company.

Steam had already been in the making prior to 2002, but its first incarnation appeared on the market in January 2003 and was directly linked to the 1.6 version of Counter-Strike, while its primary function was to ensure smooth updates and improvement of online play. The real cry of despair escaped the throats of Half-Life fans at the end of 2004, when it turned out that the long-awaited sequel to the adventures of Gordon Freeman required the Steam client and the activation of the game on a personal account. 2004 must have been a strange year for Valve – on the one hand there was the huge success of Half-Life 2 and the introduction of a completely new service on the market, and on the other there was the massive outrage of disgruntled players.

Prior to DRM #4 – Lenslok

This anti-piracy measure comes from the glory days of eight-bit machines and is based on a set of prisms enclosed in a plastic housing. The player's task was to match Lenslok with the on-screen mess until a clear symbol appeared. The fact that this system failed completely when used with too small or too large screens, and that sometimes the boxes contained Lensloks to completely different games didn't contribute to making it a fan favorite. This protection was used by Elite released for ZX Spectrum.

We all know well how this ended (or rather: how it continues to this day). Just over a decade later Steam is loved my legions. Maybe not always, and certainly not by everyone, but there is no denying that the people of Valve knew exactly what they were doing. In 2005 they signed the first partnership agreement (with Strategy First) allowing to sell games through a new distribution platform built-in in the Steam client. Overtime, more and more cooperating companies appeared – after two years 150 titles could be found on Steam, and currently this number exceeds 4500 items. A powerful store featuring regularly scheduled sales sucking money from the wallets of more than 125 million of active users proved to be a hit. Of course, under the guise of a well thought-out service lurks a highly effective DRM system.

If you want to play, you need to activate the game on your account, which, according to the official rules, you can't sell to anybody. That's not all – any detected violation of the rules can cause either a ban of the entire player's account, or limit its functionality (only allowing playing offline, removing social options, etc.), and each amendment to the rules and conditions must be accepted by the user under pain of losing access to one's library. Many people find this kind of treatment quite irksome, as well as the fact that the entire Steam is practically one big game rental and not an actual seller of property. Associated with this aspect was the recent attempt to adapt the service rules to the EU law, which allows to return goods bought via Internet within 14 days. It was cleverly bypassed by Valve through modifying a few lines in the contract. People keep complaining, but Steam is doing great and is still growing.

The effectiveness of the method of combining DRM with a community and a store has been confirmed by its followers. In 2009 Ubisoft launched Uplay (initially as a social tool and a database of achievements), which later gained a desktop application and a shop to distribute the games of this developer exclusively. Electronic Arts also created a service modeled on Steam – the players initially used the EA downloader, which later became EA Link, to finally transform into Origin in 2011. The product of EA is the main competitor of Steam and offers very similar functionalities, though its community is so far weaker in numbers (more than 50 million registered users). At some point the players were very upset with the managers of the platform when it was revealed that Origin may collect information about their activities, delete purchased games and gain access to unrelated software on the player's computer. Currently, when using this software, one must only agree to accumulating information about the hardware on which Origin was launched.

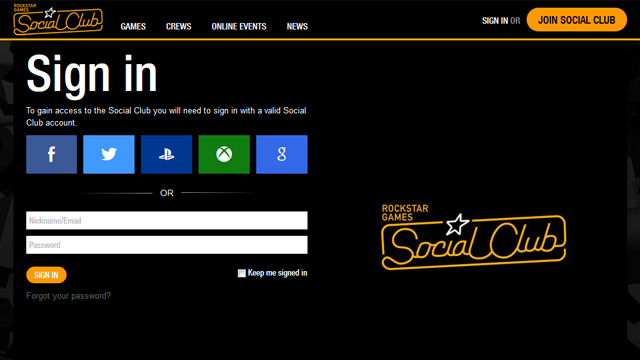

The convenience of using such systems is so far sufficient for the vast majority of users, though the question "What if servers go down or the company goes bankrupt?" remains just as relevant today as it was a few years ago. The downside is the lack of agreement between service providers resulting in bizarre situations. For example, GTA V bought on Steam first launches a Rockstar Social Club app (which is a version of DRM dedicated to the games from this developer), and only then the game. However, it seems that Steam and its counterparts are a sufficiently effective and little flawed way to deal with pirates, and we rarely hear about these services really annoying honest players. Of course, until the day comes when the million-dollar server farms get eaten by rats.

Does the perpetual struggle with pirates make sense? As long as it doesn't happen at the expense of peace of mind of people paying for games – it definitely does. However, all developers do realize that one just cannot win with breaching security measures and releasing illegal copies online. So why bother at all? It all boils down to a simple fact: the longer a new game remains "safe" after its premiere, the better it is for its developer. Even the 13 days of BioShock mentioned in this article was a very satisfactory outcome for Take-Two Interactive, not to mention the record-breaking Chaos Theory. There’s no doubt that many players frustrated by waiting for a functioning pirate version simply caved in and bought a genuine copy eventually. And in the end of the day, this is what every game developer really wants.